The Drag Queens Who Helped Little Richard Invent Rock & Roll

On Imitation

Little Richard is an amalgamation of all the queer artists who came before.

Just beyond the horizon of Manhattan and its glamorous bustle as the hopeful clamor for acclaim in industries like art, fashion, and music, there’s another island. If Manhattan is the “concrete jungle where dreams are made of,” then Hart Island is where some dreams get cast aside in an unmarked pine box. Hart Island is our country’s largest mass gravesite, owned and operated by New York City since 1869. It contains millions of lost souls, many homeless or neglected, and all buried without celebration in the city’s shadow. Workers place unclaimed corpses in meager wooden coffins, load them onto a ferry, then stack them in trenches. Hart Island welcomed a large uptick of new residents during epidemics like tuberculosis, the 1918 flu, and became notorious during the early 1980s when the newly-named AIDS virus ravaged the city’s gay population. One of the souls who now rests in an untraceable spot on Hart Island deserves our recognition as a rock & roll originator. Without Esquerita, there may never have been a Little Richard — the self-proclaimed “Queen of Rock & Roll” and perhaps its true king.

“Watching him, that’s how the Rolling Stones became the Rolling Stones.”

- Keith Richards

“Little Richard was the top of the artist food chain.”

- Nile Rodgers

Excerpts from PBS documentary Little Richard: The King and Queen of Rock & Roll

Little Richard is cited as an inspiration to a generation of rockers who followed. Nearly every white rock & roll star in the 1950s covered Little Richard’s songs, including Bill Haley, Pat Boone, Buddy Holly, Jerry Lee Lewis and the Everly Brothers. Elvis Presley covered four of Little Richard’s songs on his first two albums.

The flamboyant icon exploded the ‘50s music scene with his thunderous piano and electrifying stage presence. Little Richard’s uninhibited performances were unlike anything white audiences had ever seen, and his style would set the tone for the future of rock and roll. Everyone copied him to some degree, but Little Richard also copied from others, specifically the queer artists like Esquerita he met throughout his life.

Rock & roll was conceived in the queer, Black South where Richard learned who he was as a performer. Roadhouses, dive bars, and juke joints on the Chitlin' Circuit proudly showcased performers who gained initial fame from touring tent shows. This network of performance venues catering to Black audiences popularized blues and gospel music throughout the United States beginning in the 1930s. These new forms of music were precursors to rock & roll. (The era’s two highest-paid singers, by the way, were queer Black women, Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith.)

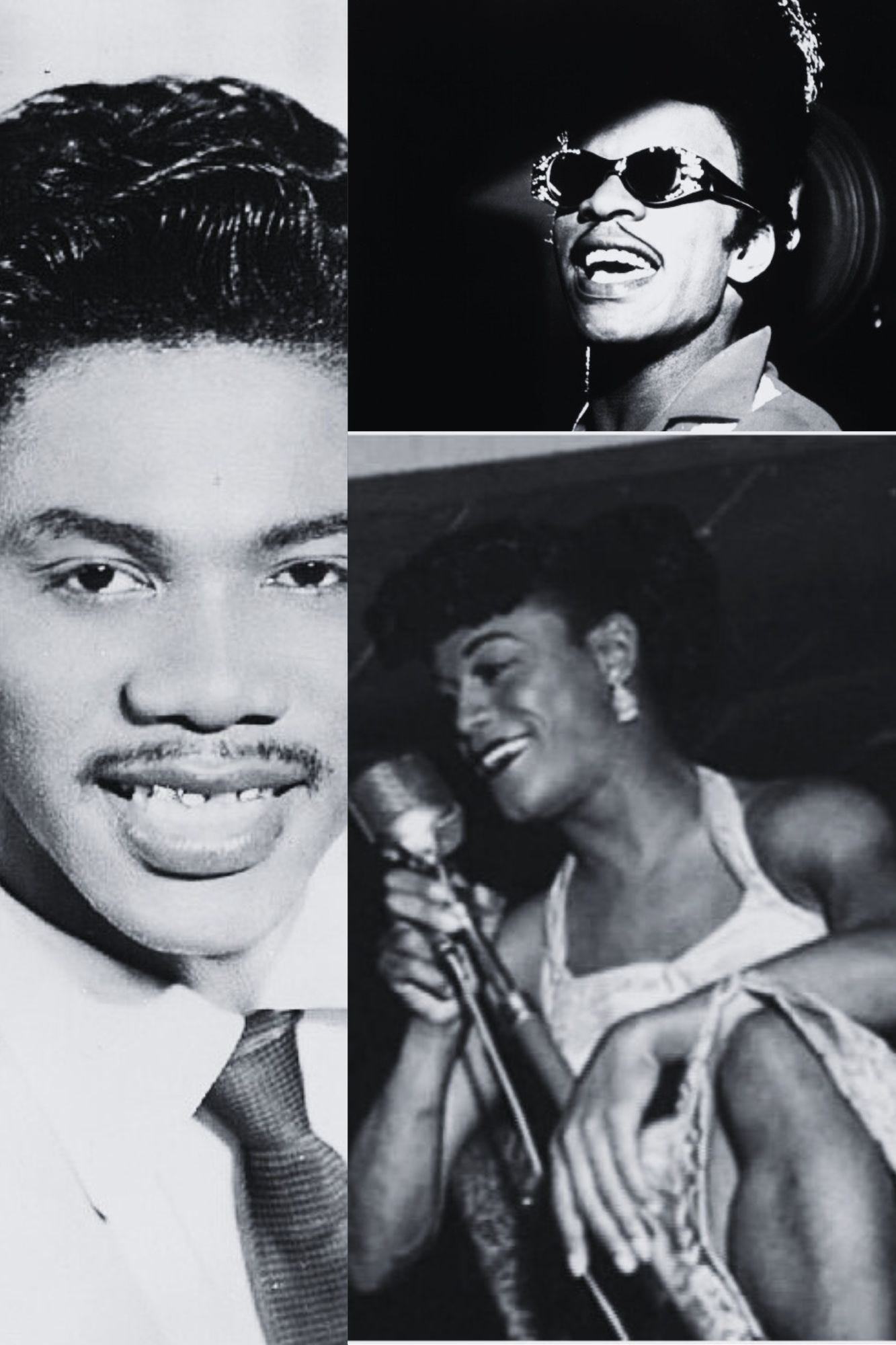

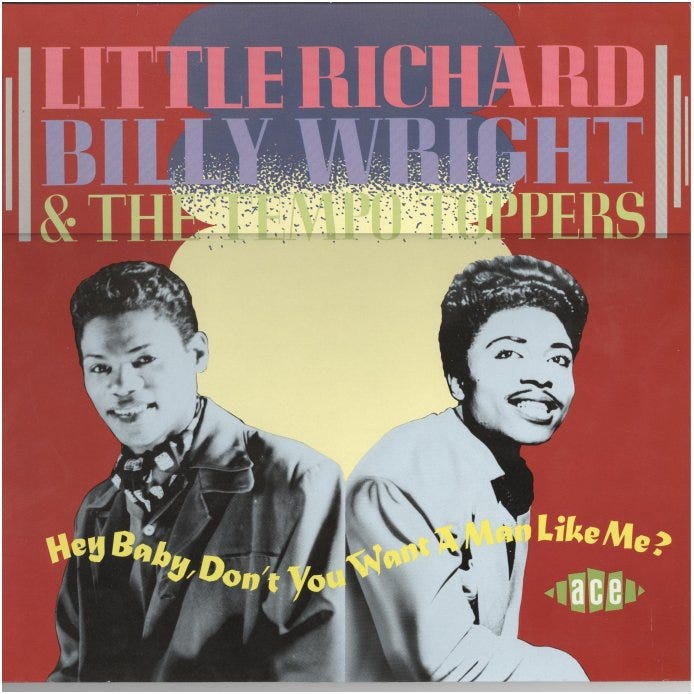

Tent shows included a variety of entertainment, and drag performers were some of the biggest draws. By age 20, Little Richard was performing as a drag queen named Princess LaVonne on the Chitlin Circuit, and he was practically already a showbiz veteran. He’d gotten his first taste for performing at age 14 when Sister Rosetta Tharpe — the queer woman who would later be called “The Godmother of Rock & Roll” — gave Richard his first paid gig in 1945. At the time, he was working the concession stand at a performance in his hometown of Macon, Georgia. When Tharpe overheard him singing backstage, she put on Richard as her opening act. In 1951, he got his second break from another queer icon, Billy Wright, known then as the “Prince of the Blues” who’d had a string of hits in the late ‘40s. Wright was also a former “tent show queen” and taught his young protege about fashion and what makeup to wear onstage. Richard’s eventual pompadour and pencil mustache was an homage to Wright’s style. Wright even got Richard hooked up with his first record deal in 1951 with RCA Victor.

Richard had recorded a couple of unsuccessful albums by 1952 when his father’s death forced him to move home to help care for his 11 siblings. Working as a dishwasher at the Greyhound station in Macon, Richard finally met the transformative queer figure who would not only change his life but the entire course of rock & roll.

“I met him at the bus station,” Richard said in an interview with KCRW. “I would sit there all night and watch people get off the bus. And he got off. All 6 feet 2 inches of him. And I said, ‘Oh boy!’”

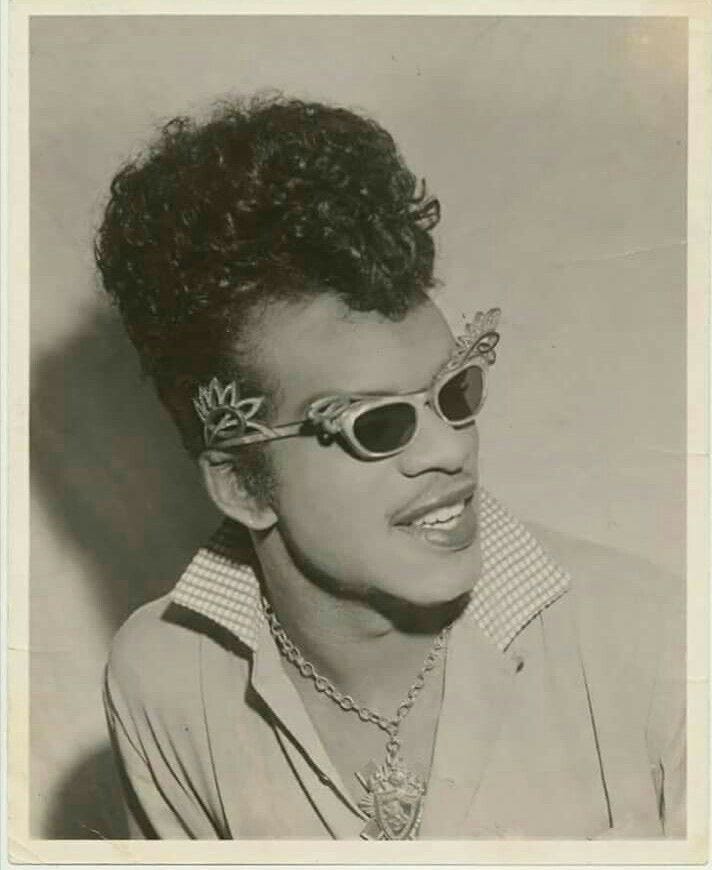

Esquerita, a prolific piano player on tour with a traveling gospel show, must have looked like he also got fashion advice from Billy Wright: heavy makeup, a high pompadour wig, bedazzled sunglasses, and a pencil mustache. After a short flirtation, Esquerita went home with Richard and taught him many things, including an explosive piano style.

“Esquerita and me went to my house and he got on the piano and he played ‘One Mint Julep.’ It sounded so pretty. The bass was fantastic. He had the biggest hands of anybody I’d ever seen.”

“Hey, how do you do that?”

“I’ll teach you,” Esquerita replied.

“And that’s when I really started playing.”

Esquerita claims to have also taught Richard those signature ad-libbed falsetto “woooohs.” In a 1983 interview with Kicks magazine, Esquerita recalled: “When I met Richard, he wasn’t using the ‘obbligato’ voice. Just straight singing.”

Said Little Richard of Esquerita: “He was one of the greatest pianists, and that’s including Jerry Lee Lewis, Stevie Wonder or anybody I’ve ever heard.”

It was a night that changed American music. Like Richard, Esquerita had started performing in church and dropped out of school to pursue music in traveling vaudeville shows. He’d developed an electric performance style by touring with charismatic gospel singers like Brother Joe May, whose religious stage show was more Chuck Berry than solemn hymns, and Sister O.M. Terrell, whose high-energy wailing surely influenced Esquerita’s indefatigable stage presence.

After his unforgettable encounter with Esquerita, Richard found himself a new band with a much heavier, thumpier, in-your-face sound and sent a demo to Specialty Records.

Maybe Esquerita could’ve been the Queen of Rock & Roll, but Little Richard beat him onto record shelves. By 1955, Esquerita was recording music with the gospel group Heavenly Echoes. That same year, Little Richard was struggling to find a hit with Specialty Records. Producer Robert Blackwell joined Richard in New Orleans, thinking he might be the next Ray Charles or Fats Domino, but the recording session was a bust. Frustrated, the men decided to take a break over at the Dew Drop Inn, a famous venue on the Chitlin Circuit that Richard had performed at years before as a drag queen. Recalling his roots, Richard plunked out a bawdy tune he’d honed on the circuit called “Tutti Frutti/Good Booty.”

Tutti Frutti, good booty

If it’s tight, it’s alright

If it’s greasy, it makes it easy

The wild rhythm and falsetto yowls that Richard had learned from Esquerita stunned Blackwell. This was a hit. But first, they had to clean up the X-rated lyrics. “Tutti Frutti” went to No. 2 on the R&B charts. The next year, “Long Tall Sally” reached No. 1. Little Richard was a superstar.

“I think Little Richard copied off him a lot, but Little Richard got to the studio first,” recalled Lightin’ Lee, a New Orleans guitar player who knew both Richard and Esquerita, in an interview with Oxford American.

Richard’s fame was a difficult pill for Esquerita. The world was barely ready to handle one Little Richard, let alone two. The man who had lent his electric piano playing style and fashion tips would now be seen as a Little Richard imitator. “I had to figure out something I could do that was different, something that would identify me. I knew, with that done, I could sell myself and make a bunch of money,” he said to Kicks. So, Esquerita did a strange thing for an aspiring rock star. He left New York and returned to Greenville, South Carolina. “That’s where Esquerita was created.”

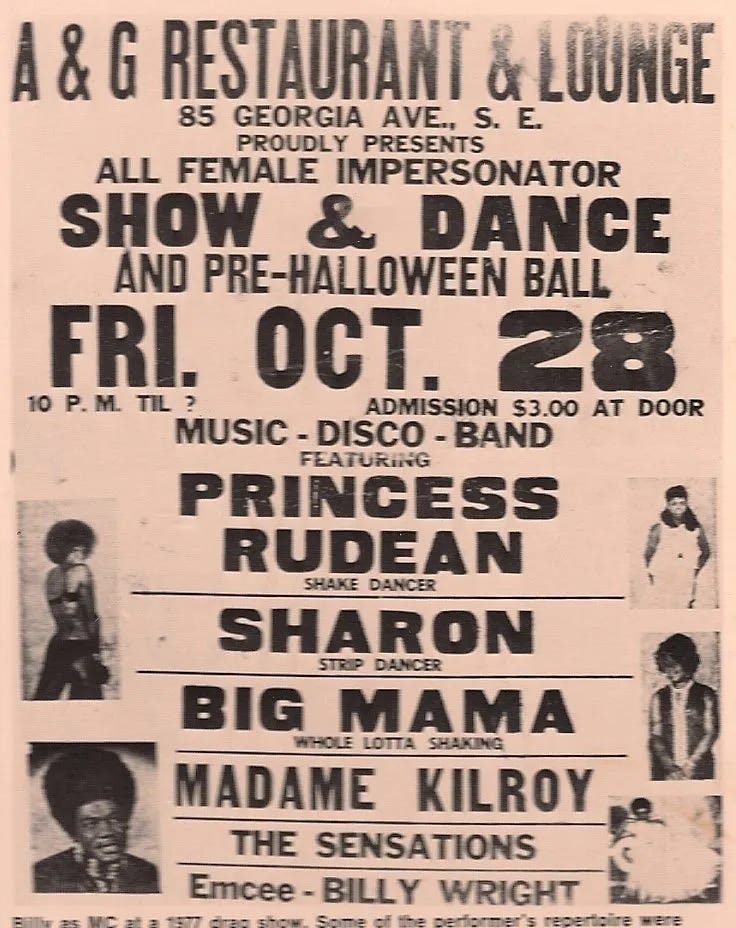

He got a job playing at the Owl Club on Washington Street and went by a new stage name, Professor Eskew Reeder. White patrons were allowed into the Black clubs, and one night a member of the rockabilly group the Blue Caps, Paul Peek, caught the show. Meanwhile, Little Richard, who had reached the pantheon of rock stardom, had just quit music to pursue religious life. Richard was touring with the Blue Caps when God told him to quit showbiz. So when Peek discovered Esquerita in Greenville, he was convinced he’d found the perfect replacement. That led Capitol Records to sign Esquerita and release his first singles in 1958, followed in 1959 by an entire album, “Esquerita!” The songs were like Little Richard on steroids. The lyrics were as unfiltered as Richard’s were before being edited for mainstream audiences. Take the lyrics to “Hey Miss Lucy.”

Hey Miss Lucy

You’re too fat and juicy for me

Woooh

Hey Miss Lucy

I tell you why I treat you wrong

Because you’re too fat

Ought to get some of that meat off your bones

Another song, “Esquerita and the Voola,” literally has no words. He just howls “WOOO WOOOO” throughout the entire song. The notes on the back cover of Esquerita declare the music as “truly the farthest out man has ever gone.”

The general public wasn’t ready for the unedited, queerest version of Little Richard. The album failed to chart, and Esquerita was dropped by Capitol Records. For the next decade, he would bounce around the outskirts of the music business, performing regularly at the Dew Drop Inn, where Richard famously christened rock & roll with “Tutti Frutti.” He even recorded with Berry Gordy before Gordy founded Motown Records. Gordy was searching for a new sound and invited an ensemble crew of musicians from New Orleans. “That’s when the Gordy sound changed,” Esquerita said to Oxford American. “We just started jammin’, payin’ no mind, carryin’ on, and Berry taped us right there in Hitsville, USA.” Motown’s new sound may have been influenced by Esquerita and his compatriots, but it didn’t land him a record deal with the fledgling label.

By the 1970s, Esquerita would find himself crossing paths once more with Little Richard, who had returned to rock & roll. In 1969, Esquerita wrote “Dew Drop Inn,” about the New Orleans club, and Little Richard recorded it, along with another Esquerita number called “Freedom Blues.”

But for the next dozen or so years, Esquerita sunk further into obscurity and might’ve disappeared completely if it weren’t for a group of influential white kids obsessed with rare albums. Miriam Linna, one of the founding members of the punk band the Cramps, had started a magazine devoted to rock music outsiders called Kicks. She and her partner Billy Miller, had also started a small record label called Norton Records. They featured Esquerita on the cover of Kicks and were going to release some of his old demo recordings.

According to Oxford American, when Linna brought a gay friend to see an Esquerita soundcheck, the friend said, “Oh my god, that’s Fabulash,” whom he described as “one of the most vicious drag queens that he ever met . . . a really, really overpowering entity.”

Before the album could be released, though, Esquerita died. His last communication with Linna was a message on her answering machine. “I’m at the hospital, bring me some rice and beans. Rice and beans.”

Esquerita was one of the 2,710 people in New York to die of AIDS in 1986. He is buried in an unmarked grave on Hart Island.

Rock & roll history is filled with examples of the Black and queer folx whose names have been omitted by gatekeepers, buried outside of history books in unmarked graves. Little Richard is the “Architect of Rock & Roll,” and laid the foundation for generations of imitators. But there would be no Little Richard without the queer performers and tent show queens who doused him in makeup, taught him those X-rated songs, and shined him up to be a star.

If you’ve learned something from this publication, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. We’re offering a 40% discount during Pride month.

Read our full tribute to Little Richard here:

I wish there was a way to return Esquerita to his native South Carolina, with all the appropriate fanfare and statuary he deserves. Maybe this beautiful piece is the beginning of a movement to make that happen!

Great piece of an (for me) unknown star who deserved so much more. It's important these stories are told.