Erotica - Madonna

How Madonna’s Erotica Helped Queer Culture Survive the ’90s

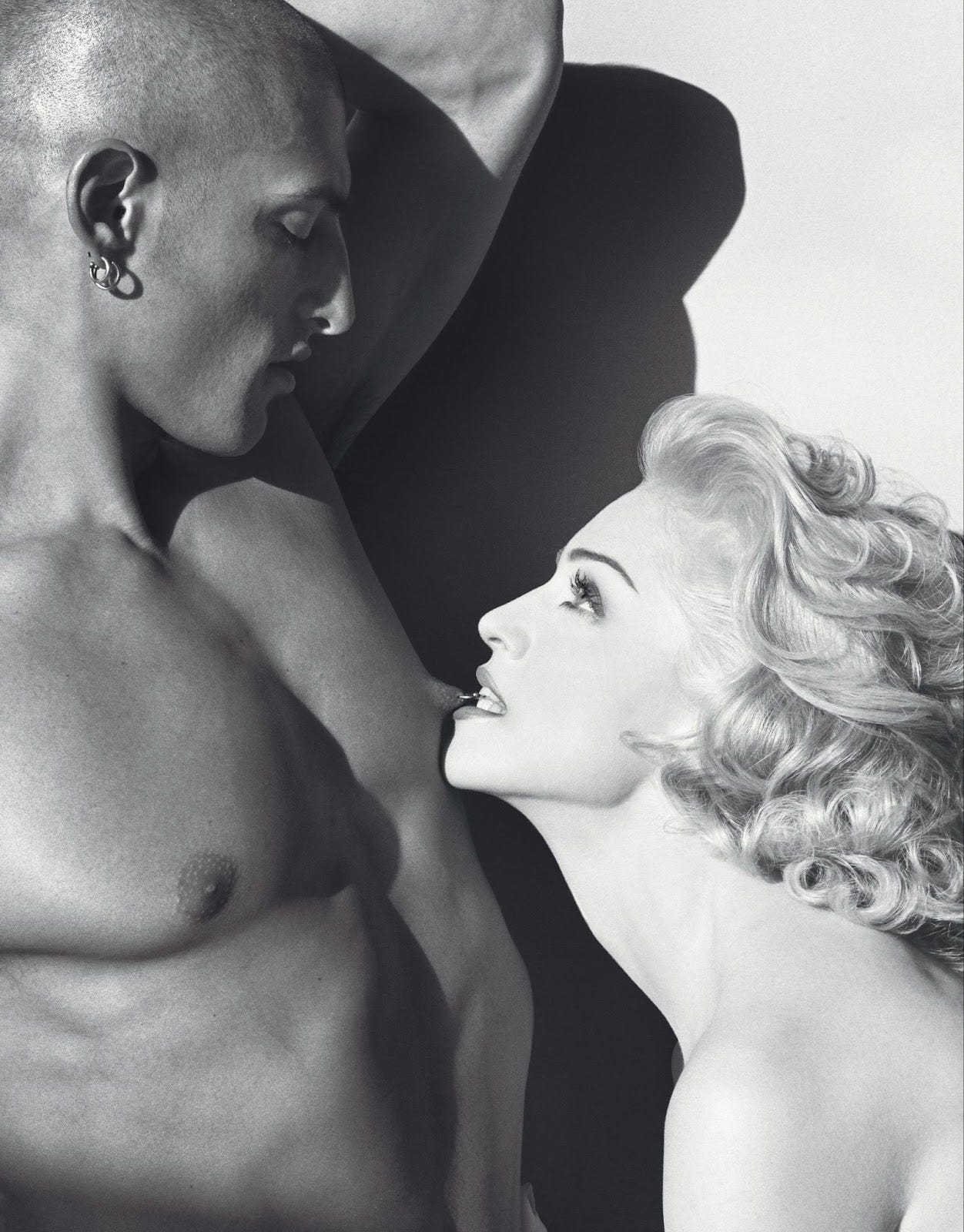

At the height of her fame, Madonna did something unthinkable for a mainstream pop star: she released an album and a photo book that centered sex—queer sex, kinky sex, lonely sex, grieving sex. It was the height of the AIDS crisis, and the culture’s response to desire was fear. But Erotica wasn’t afraid. It was tender. It was messy. It was defiant.

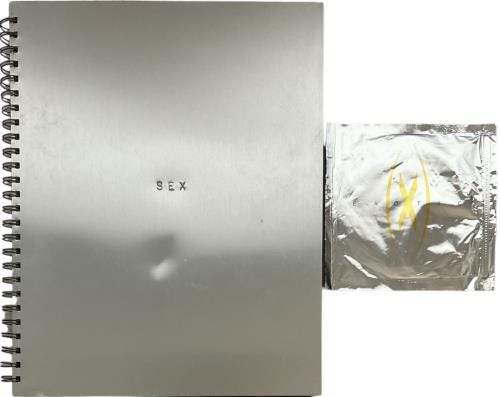

By the end of 1991, more than 33,000 people had died of AIDS-related complications. It was the second leading cause of death among people between the ages of 25-44. As the epidemic raged into its second decade and the ashes of the moral majority smoldered at the end of the Reagan/Bush era, Madonna released her fifth studio album, Erotica. Arriving alongside her metal-bound, finger-licking coffee table book Sex, the project detonated into a culture that wanted sex to stay closeted, especially queer sex. But Madonna offered something radically different - she turned shame into spectacle, fear into fantasy, and grief into dance music.

Conservatives were quick to label her vulgar, perverse, irresponsible. But Joseph Ryan- Hicks from Attitude offered another perspective. “What many critics failed to recognise at the time was that although Erotica was provocative, at its core were messages of safe sex and liberation at a time when people needed to hear them the most.” From the Evening Standard, El Hunt wrote: "Both Erotica and Sex came out at a time when certain kinds of sex—specifically queer sex—were steeped in debilitating amounts of shame and fear. By putting forward a vision of sexual exploration that often feels cold, detached, and uneasy, Madonna flawlessly captured the emotional disconnect of searching out an intimacy that has suddenly become deadly.”

In that context, Erotica wasn’t just pop rebellion. It was survival.

My name is Dita, I'll be your mistress tonight

I'd like to put you in a trance

If I take you from behind, push myself into your mind

When you least expect it, will you try and reject it?

If I'm in charge, and I treat you like a child

Will you let yourself go wild, let my mouth go where it wants to?

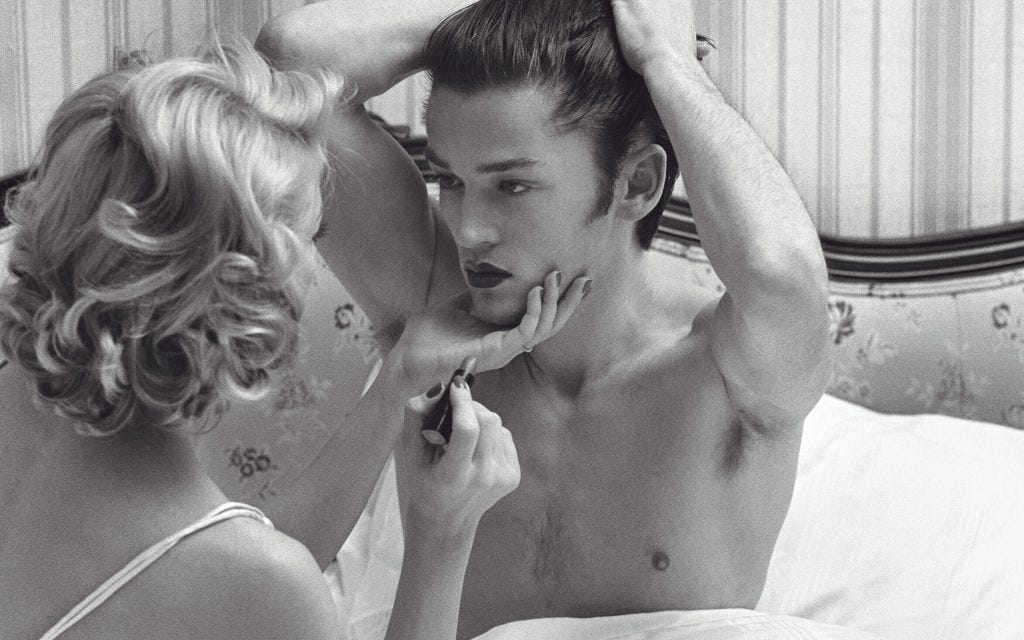

The album’s opening title track introduces Mistress Dita, Madonna’s dominatrix alter ego, commanding submission over a gritty blend of New Jack Swing and house. In the video, Dita acts out her (and maybe your) sexual fantasies with a host of celebrities. She makes out with Isabella Rossellini on the beach. She has a threesome with Naomi Campbell and Big Daddy Kane. She has a threesome with two butch bald lesbians. She goes to a leather bar and dons a ball gag and harness. The video is a more PG-Rated version of the Sex book.

But Erotica isn’t a mere S&M playground. What follows across the album’s 13 tracks is something far more complex: vulnerability, loss, yearning.

On “Bad Girl,” she sings of chain-smoking and casual sex as coping mechanisms for heartbreak. “In This Life” is a requiem for friends lost to AIDS.

Have you ever watched your best friend die [what for]

Have you ever watched a grown man cry [what for]

Some say that life isn't fair [what for]

I say that people just don't care [what for]

They'd rather turn the other way [what for]

And wait for this thing to go away [what for]

Why do we have to pretend [what for]

Some day I pray it will end

On “Why’s It So Hard,” she pleads for empathy in a world numbed by prejudice.

I'm telling you brothers (Brothers), sisters (Sisters)

Why can't we learn to (Why's it so hard?) challenge the system

Without living in pain?

Brothers (Brothers), sisters (Sisters)

Why can't we learn to (Why's it so hard?) accept that we're different

Before it's too late? (Why's it so damn hard?)

And on “Deeper and Deeper,” beneath the disco sheen, there's a hunger for connection, not just carnality. These aren't mere club tracks. They're diary entries from the edge of the apocalypse.

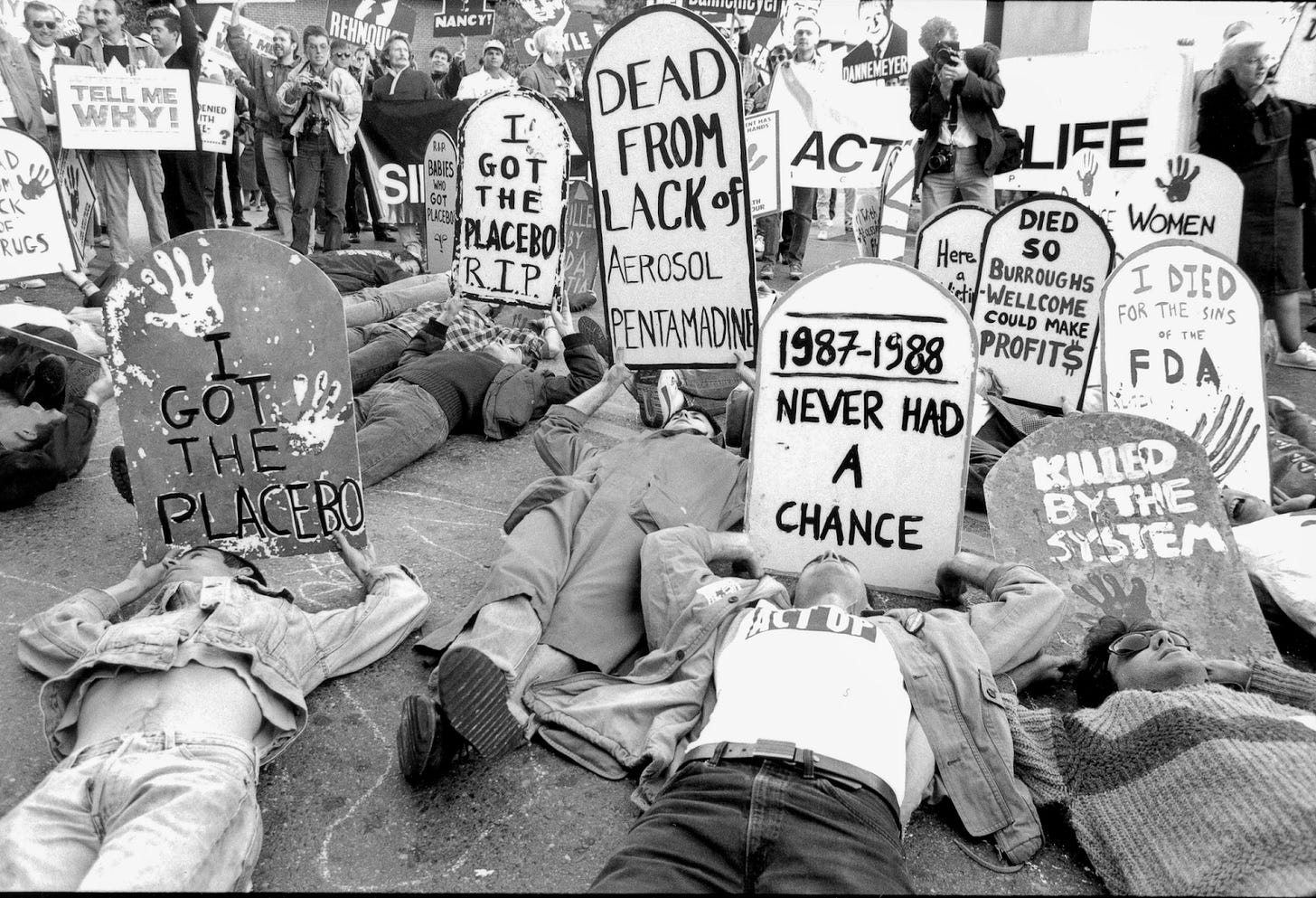

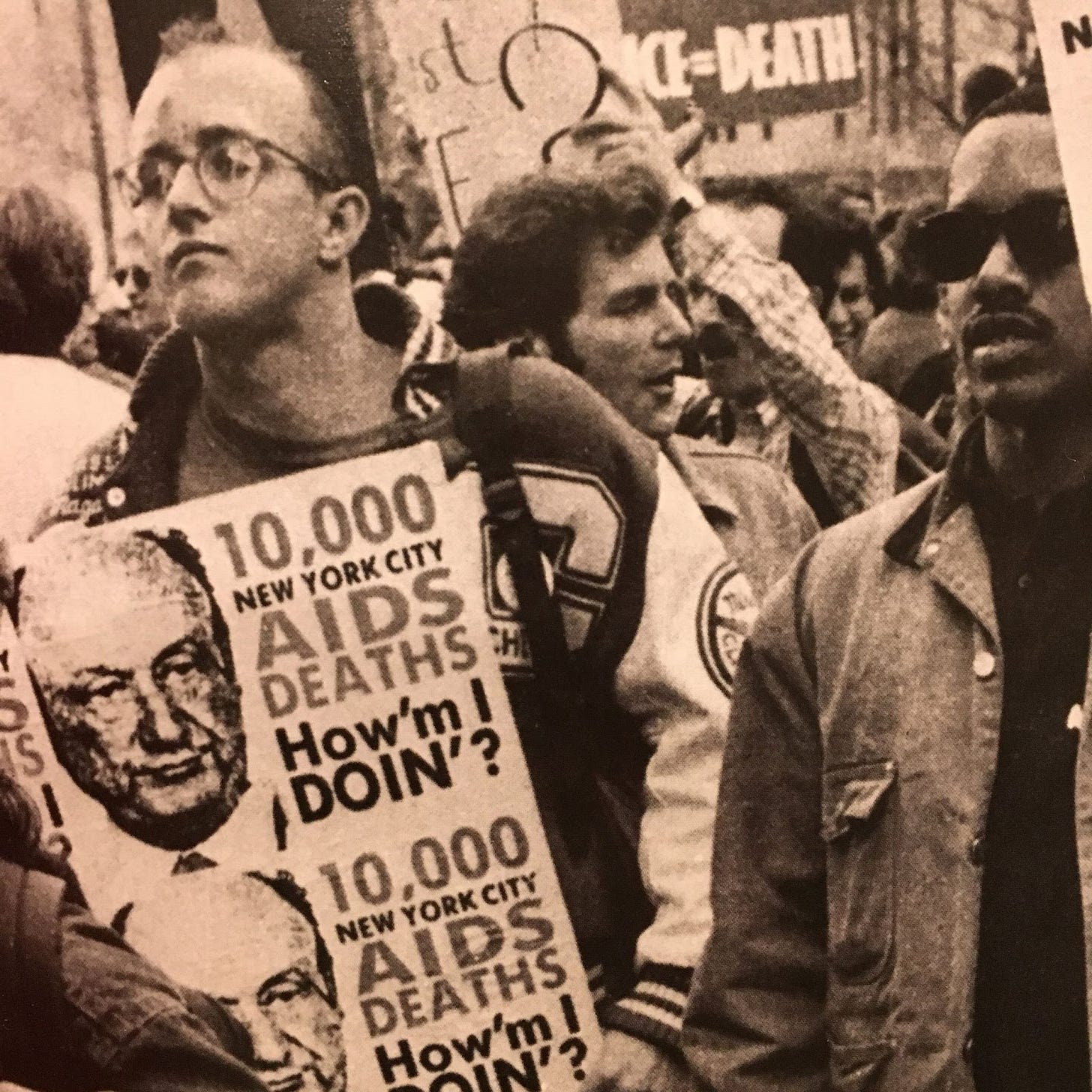

Erotica emerged at a moment when queer culture was under siege. ACT UP was taking to the streets. The U.S. government was willfully neglecting a public health crisis that was devastating gay communities. And Madonna—unlike many pop stars—didn’t look away. She had already channeled the underground queer ballroom scene in “Vogue,” a smash hit that brought Black and Latino queer aesthetics to MTV’s doorstep, though not without criticism. Madonna’s visibility afforded her a level of protection not shared by the communities she borrowed from. Still, in a pre-Internet era, Madonna served as a rare mainstream vessel for queer representation. She was, as some dubbed her, the first pop megastar to give queer imagery mass-market visibility. In that sense, Erotica is more than just music. It's documentation. She was also vocal about her allyship in interviews. Most notable, in a two-part interview with The Advocate in 1991, she criticized homophobia in the music industry. According to The Advocate themselves, it was the first time a worldwide celebrity did an interview with a national gay magazine. Madonna addressed homophobia again that year during an interview in Good Morning America saying: "I deal with a lot of issues ... and what I think to be a big problem in the United States and that is homophobia.”

Before she was the Queen of Pop, Madonna was a Lower Manhattan regular—steeped in the queer punk and disco scenes that Nan Goldin photographed and Robert Mapplethorpe mythologized. By the early ’90s, AIDS had already taken many of those artists, including her close friend Keith Haring and Blond Ambition dancer Gabriel Trupin. The loss was personal, and it’s embedded in Erotica’s DNA.

Just as Beyoncé’s Lemonade was forged in the crucible of Black Lives Matter, Erotica was born of ACT UP’s outrage and grief. It’s a love letter to a disappearing world—and a defiant refusal to let that world vanish without celebration.

Madonna has always been a lightning rod accused of appropriation, praised for allyship, heralded as an icon, and dismissed as opportunist. Michael Dango, professor of queer and feminist theory at Beloit College and author of the book Erotica, urges us to resist the binary of hero or villain. “It’s not the case that she either has to be praised or scorned,” he says. “It’s about spelling out what she made possible for marginalized communities at the same time that she obviously had other motives for doing that, including making a lot of money.” In his article for Psychology Press, Brian McNair added that, by "dabbling in the pornosphere" with Sex and Erotica, Madonna took a financial risk with her career, and it wasn't until the release of 1998's Ray of Light that her record sales went back to "pre-Erotica" levels; nonetheless, the author concluded that, "what she lost in royalty payments, she more than made up for in iconic status and cultural influence.”

This nuance is essential. It allows us to honor what Erotica did—and still does—for queer listeners without ignoring the privileges Madonna leveraged in its creation.

In the 30-plus years since Erotica’s release, the conversation around sex, queerness, and pop music has shifted—but Madonna’s impact still reverberates. She may not have always gotten it right. She may not have belonged to every community she celebrated. But she showed up. Loudly. Unapologetically. Sensually. Sentimentally.

“I think the problem is that everybody’s so uptight about sex that they make it into something bad when it isn’t, and if people could talk about it freely, we would have people practicing more safe sex,” she told Vanity Fair in 1991. “We wouldn’t have people sexually abusing each other, because they wouldn’t be so uptight to say what they really want, what they really feel.”

For a generation growing up in silence and stigma, Erotica was a siren song. A way to survive. A way to remember.

I don’t hide any content behind a paywall. To support my work, consider upgrading to a paid subscription or making a one-time donation.

This is an amazing write up and, as someone who turned 20 at the time Erotica was released, it all rings so true. It was not appreciated in its time and was massively overshadowed by the book (from which it cannot and should not be separated) but it was a gigantic gamble on Madonna's part that I think took three decades to really pay off.

Erotica is a great album. I loved how artists like her weren't afraid to express their sexuality in an era of AIDS. This also makes me think of George Michael and how he released "I Want Your Sex."

The radio stations hated him for saying "sex" on a record, but he didn't care. It was a song about monogamy. That's probably why Madonna liked George.