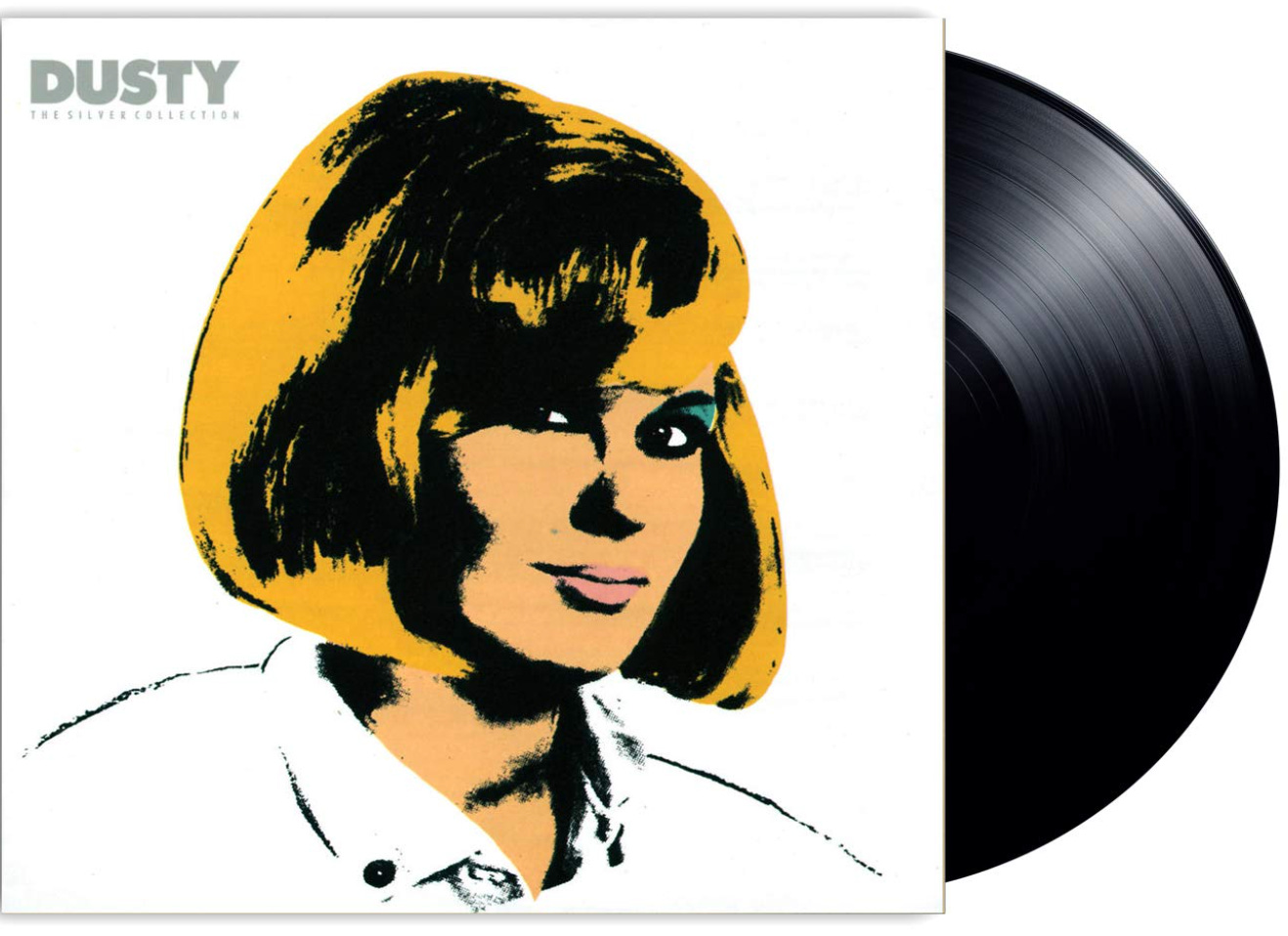

"Son of a Preacher Man" - Dusty Springfield

On Imposter Syndrome

A queer icon struggles to face her demons.

Inside the confines of a 1950s childhood bedroom, portraits of Hollywood starlets like Betty Grable and Marilyn Monroe adorn the walls. Young Mary, barely a pre-teen, imagines her hairbrush as a microphone and belts standards by Billie Holiday. She waves and blows kisses at her fawning public in the mirror. But as her eyes refocus and get a closer look, the person staring back in the mirror isn’t a blonde bombshell. She’s a slightly overweight tomboy with a genderless haircut and government-issued prescription glasses. Mary O’Brien, nicknamed “Dusty” because she’d so often get dirty playing sports with the boys, is a nobody.

And if the whispers coming from that reflection in the mirror had won, you might not know Dusty Springfield’s music today. Except that the songs are iconic, instantly recognizable. Her voice is synonymous with today’s silver screen. You inadvertently conjure cinematic imagery by mentioning any of her hits:

“Son of a Preacher Man” — Pulp Fiction

“Wishin and Hopin” — My Best Friend’s Wedding

“The Look of Love” - Casino Royale, Catch Me If You Can, or Austin Powers

“Spooky” — Lock, Stock, and Two Smoking Barrels, or Ant-Man and the Wasp

Although most of her hits were recorded in the ‘60s, you know the music, maybe even recognize the signature peroxide blonde bouffant. But Dusty Springfield — or rather Mary Isobel Catherine Bernadette O’Brien — is nowhere to be heard in these hits because they weren’t written by her and don’t sing her life. Her more complicated reality was disguised behind the wig and fawning lyrics about men. In real life, she was queer. And the persona Springfield created was both a safe space and a prison.

Growing up in the West Hempstead neighborhood of London, the young tomboy was known for using humor to deflect attention from her appearance. Her parents, trapped in a loveless marriage, fought constantly. Her mother was an alcoholic and her verbally abusive father would often call her “ugly.” At Catholic school, the nuns thought she was “plain” and might end up as a librarian.

Dusty believed every insecurity she was taught — that she wasn’t attractive enough or talented enough or interesting enough. Severe depression led to self-harm by cutting.

The only passion the family shared was music. When her parents weren’t fighting with each other, they introduced Springfield to jazz, blues, and showtunes. Her jealous father’s unrealized dream of becoming a concert pianist, though, led him to bully her constantly as her talents as a singer blossomed.

The awkward girl with glasses was desperate to become someone new. She dyed her hair blonde at the age of 17, put on false eyelashes, poured into sexy dresses and assumed the persona of a prom queen. This became the costume she wouldn’t take off.

“I invented a person at the age of 17 to become… and it became a monster. I lost touch with whoever was underneath it,” Springfield is quoted in biography, Just Dusty.

Or as Juliana Smith writes in The Queer Sixties, Springfield “pushed accepted notions of femininity to absurd extremes and, paradoxically expressed and disguised her own unspeakable queerness through an elaborate camp masquerade that metaphorically and artistically transformed a nice white girl into a black woman and a femme gay man, often simultaneously."

With an armor of shellacked hair and heavy makeup, Springfield first gained notoriety in 1958 with girl group the Lana Sisters, and then again with a folk band her brother started, The Springfields. By 1963, she’d fallen in love with rhythm and blues music and decided to go solo. Heavily influenced by the Shirelles and the Ronettes, her first major hit, “I Only Want to Be with You,” captured American audiences at exactly the right moment. The single was released just a week after breakout hit, “I Want To Hold Your Hand” by fellow Brit newcomers, the Beatles. Springfield was perfectly positioned at the forefront of the British Invasion and her popularity soared. The single was the first ever debuted on fledging British music television show, Top of the Pops. By 1964, Springfield had charted five more singles including two Burt Bacharach covers, “Wishin’ and Hopin” and “I Just Don’t Know What to Do with Myself.”

Quickly dubbed by journalists, “The Queen of White Soul,” Springfield’s singing style was heavily influenced by Black artists of the 1950s and early ‘60s. “She had a great respect for and an extensive knowledge of soul, gospel and R&B, so she was never just a white woman appropriating another culture,” says Bishi, a musician and performance artist in an interview with BBC. Early in her career, Springfield committed herself as an anti-racist by refusing to play for segregated, white-only audiences in apartheid South Africa. She was among the first artists whose tour contract stipulated she would not perform under segregated rule. Her tour was abruptly cut short, though, and she was deported by the government after performing for an integrated audience in Cape Town. “All I know is that anyone who wants to buy a ticket should be able to do so, “ she told reporters.

Springfield was also the first to introduce Motown musicians to English audiences by hosting a special on the television show Ready, Steady, Go! that featured Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, the Temptations, Stevie Wonder, the Supremes, and Martha and the Vandellas. “She made it possible for Motown to have success here. That’s really a historical moment that changed music forever,”said Nona Hendryx of the group Labelle in the documentary Just Dusty.

As Springfield’s career continued to soar throughout the ‘60s, gossip about her perfectionism in the recording studio circulated. Even though she couldn’t read or write music, Springfield produced most of her early hits (though she didn’t list herself in the credits). Springfield was often labeled “difficult” or a “diva” by chauvinistic male session players who weren’t accustomed to a woman having so much control over the production.

Rumors also began spreading about her personal life. She was hounded by the press for never being seen publicly with a boyfriend, and she evaded questions about marriage. In 1970, in an act of bravery — or perhaps desperation to finally be seen for the person underneath the beehive — Springfield came out as bisexual during an interview with the London Evening Standard.

“I know I’m perfectly capable of being swayed by a girl as by a boy. More and more, people feel that way and I don’t see why I shouldn’t.”

Dusty Springfield was the first major star to come out of the closet. Her revelation came before the glam rock bisexuality of David Bowie, Lou Reed, or Elton John. It was the same year that fellow UK artists, the Kinks, wrote their ode to transgender love in their hit song, “Lola.” Although she finally spoke her truth aloud, honesty came at a cost. Throughout the ‘70s, Springfield’s popularity deteriorated. She wouldn’t have another hit single for 15 years. She struggled to reconcile her ultra-feminine public persona with a private life defined by long-term relationships with women. The demons of self-hatred she’d outrun since childhood continued to haunt her. Bouts of severe depression and substance abuse landed her in the hospital after cutting her wrists. And she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

As The Queer 60’s puts it: “While today it seems a truth universally acknowledged that the ‘Swinging Sixties’ was an era of great sexual license that liberated everyone's libido from the restraints of bourgeois morality, the sexual freedom the decade brought forth was primarily for the benefit of heterosexual men. In the years before Women's and Gay Liberation, those who were neither male nor straight remained at best nonentities and at worst monsters, particularly in the generally homophobic world of rock music.”

Though Springfield’s popularity with mainstream audiences dissipated after she came out, the queer community lauded her as a hero. Drag queens began copying her signature beehive and dark eye makeup. “Basically I’m a drag queen myself,” Springfield was once quoted. At the Royal Albert Hall during a charity concert which was attended by Princess Margaret, the queer icon noted the large number of gay people in attendance. “I’m glad to see that the royalty isn’t confined to the box,” she joked about the “queens” in her audience. The princess, who was rumored to have had a secret fling with Springfield, took the remark as a personal insult. Springfield was forced to sign a letter of apology to Queen Elizabeth.

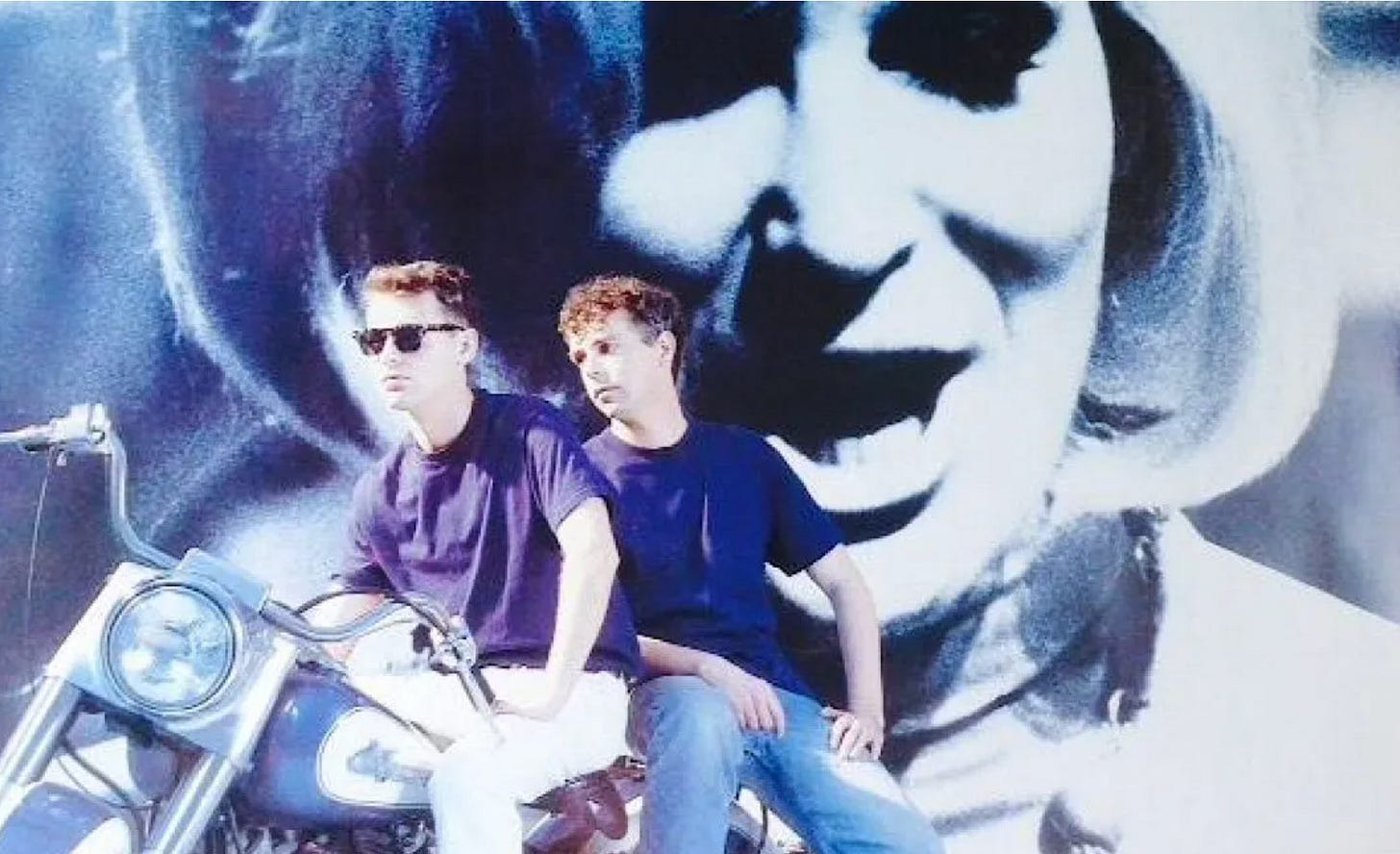

Perhaps the most significant example of support from the queer community came when the new “it” band of the 1980s, The Pet Shop Boys, asked Springfield to collaborate with the gay duo. By the early ‘80s Springfield’s career seemed destined for obscurity, prompting their 1987 hit single, “What Have I Done to Deserve This?” — which reached No. 2 on both the U.S. and UK charts.

You always wanted me to be something I wasn’t

You always wanted too much

Now I can do what I want to forever

How’m I gonna get through?”

In one fell swoop, The Pet Shop Boys — Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe — had revived their hero’s career. They would go on to produce several tracks on Springfield’s 1990 album, Reputation, which was well received in Europe. Songs like "Born This Way" (which shares its title with another by present-day queer icon Lady Gaga) along with lyrics such as "Who cares what they're whispering, whispering, whispering" ("Reputation") and "What you're gonna say in private / What you're gonna do in public" ("In Private") were finally describing Dusty Springfield’s actual life. She was beginning to stare down her demons.

Unfortunately, just as Springfield’s career was being revitalized by her queer fanbase and hipster movie directors like Quentin Tarantino, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Despite rigorous treatment, she succumbed to the disease a few weeks shy of her 60th birthday in 1999. This immense talent who was so consumed by self-doubt had died 13 days before the honor of being inducted into the Rock n Roll Hall of Fame. Elton John gave the induction speech, and Melissa Etheridge sang Springfield’s hit "Son of a Preacher Man.” The Advocate later described the performance as “a proudly out-of-the-closet lesbian singing about ‘the only boy who could ever teach me’ in honor of a woman who was required by convention to sing covertly about her real-life loves.”

Dusty Springfield was a badass. Full stop. But she spent life believing the lies whispered by inner demons. Despite being canonized as one of Rock n Roll’s best vocalists, she obsessively compared herself to others. Despite being a hero to the queer community for being out, she felt too ashamed to embrace love. Her story is tragic but her legacy says to all of the tomboys, the obedient Catholic school kids, the crippling self-doubters: you are beautiful. Do not let the demons win.

It’s so easy when know the rules. It’s so easy, all you have to do is…

Name the other queer icon whose career was resuscitated by The Pet Shop Boys:

A) Cher

B) Judy Garland

C) Liza Minnelli

D) Barbara Streisand

(Scroll to the bottom for the answer.)

And you’re a material girl.

Welcome to our merch store! Every week, we’ll offer some cool swag based on the artist from each issue.

Quiz Answer: C- Liza Minnelli. The Pet Shop Boys produced her 1989 album Results. Minnelli’s cover of “Losing My Mind” from the musical, Follies, reached #6 on the UK charts.

Did you catch our two-part series on David Bowie? You can access our full archive of articles here.

Really remarkable article, Jami! I'm embarrassed by how little I knew about Dusty (whom I've always loved), and now enlightened by how much you shared about her! Plus, I discovered a couple new Pet Shop Boys videos I'd not seen before, AND discovered they just released a new box set a couple months ago! Again, very impressive...I believe a hearty and sincere "brava!" is called for!

An excellent essay. Really informative. I loved her voice, and all of her records.