"I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)" - Whitney Houston

On The Parts We Hide

A singular talent whose demise came from the masks she was forced to wear.

It’s 1989, and Whitney Houston sits in the audience nervously awaiting the results of the “Best Single” category of the third annual Soul Train Awards. She’d already won two Grammys and 11 American Music Awards. But here, she’s visibly uncomfortable.

As nominees are announced, the auditorium erupts with emphatic screams for each competitor — Anita Baker, Karyn White, and Vanessa Williams. Suddenly, the tone shifts with Houston’s name. The audience stops clapping and begins booing.

“Sometimes it gets down to ‘You’re not black enough for them. You’re not R&B enough. You’re very pop,” remembered Houston in an interview with Katie Couric. “The white audience has taken you away from them.’”

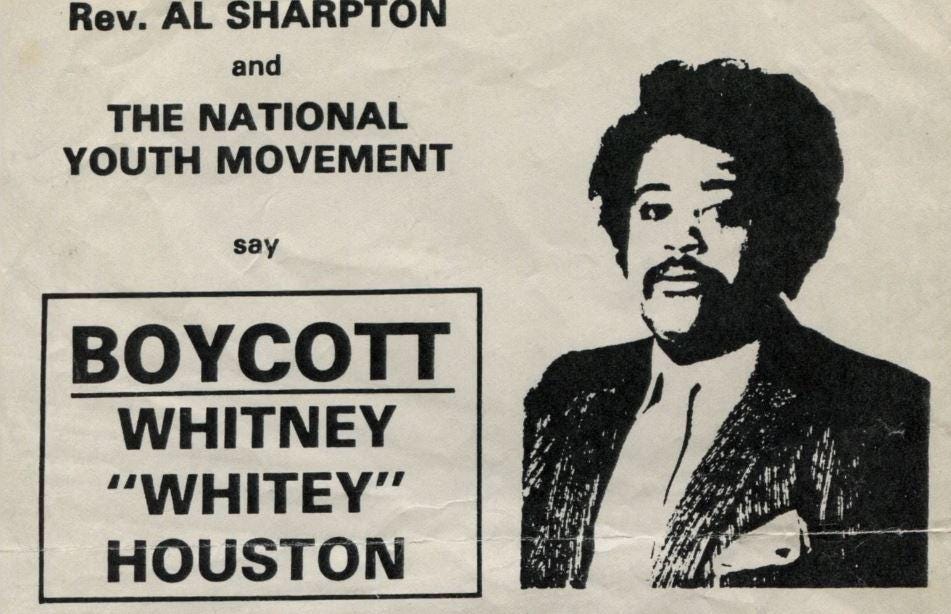

Despite Houston’s mega-success, Black audiences were calling her a “sell out.” Many radio stations stopped playing her music. Partly it’s because Houston was marketed intentionally by Clive Davis and Arista Records to appeal to white audiences. “Anything that was too ‘black-sounding’ was sent back to the studio,” Arista’s head of promotion says in the documentary, Whitney: Can I Be Me. “We didn’t want a female James Brown.”

Whitney Houston has always been an icon in the queer community. Gay men in particular have found strength in divas with big personalities and big voices to match, and no voice compares to Houston’s. But even in all that power, even as she emboldened others to be who they are, she might never have felt fully herself. And, exploring her identity as a Black woman wasn’t the only challenge.

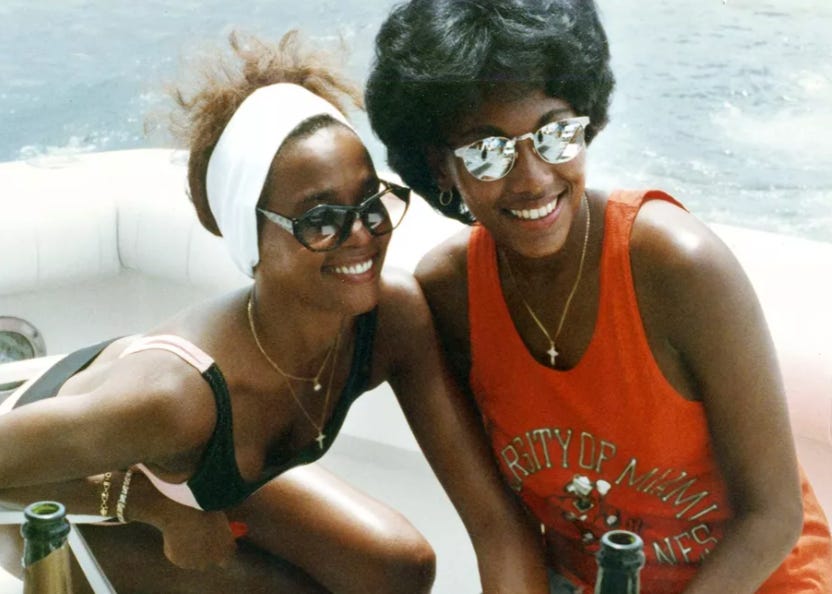

When Houston was crowned pop’s princess, tabloid chatter about her sexuality was immediate. She was never seen without Robyn Crawford — the bestie turned assistant turned creative director, whom Houston met at summer camp when she was 16. It was Crawford in the paparazzi photos, at the meet-and-greets, the plus-one at events. Crawford even appears in the music video for “You Give Good Love,” Houston’s first single in 1985.

Queer actor and creator of the Showtime series, The Chi, Lena Waithe, took notice of the palpable bond between Houston and Crawford. "I grew up watching Whitney Houston on TV, but I would always zero in on you,” Waithe said of Crawford. “You've got to be special for somebody to look past Whitney Houston and go 'Who's that?'"

Houston was a devoted ally to the LGBTQ+ community throughout her career, though she repeatedly denied rumors she was bisexual. She surprised fans with a performance at the New York Lesbian and Gay Pride Dance in 1999. In 2000, she appeared on the cover of Out magazine. When asked about the rumors, Houston replied: “I suppose it comes from knowing people… who are. I don’t care who you sleep with. I have friends who are in the community. And I’m sure that in my days of bein’ out, hanging with my friends, having nothing but females around me, something’s gotta be wrong with that. I love everybody. If I was gay, I would be proud to tell you, ’cause I ain’t that kind of girl to say, ‘Naw, that ain’t me.'”

Five years after Houston’s tragic death, two documentaries featuring interviews from her inner circle hint that she did have an intimate relationship with Crawford — who today is married to a woman, and who eschews labels for her own sexuality. Both 2017's Whitney: Can I Be Me and 2018's Whitney highlight the familial homophobia that surrounded Houston, and the pressure she felt from the entertainment industry to maintain her image. In Whitney, Houston’s brother Gary, made explicitly homophobic comments about Crawford: “She was something that I didn’t want my sister involved with. It was evil, it was wicked.”

In 2019, Crawford broke her silence about their relationship in her memoir, A Song For You. She revealed that as teenagers, the pair had a sexual relationship that lasted for two years.

She wrote, "It wasn't all about our sleeping together. We could trust each other with our secrets, our feelings, and who we were. We were friends, we were lovers.”

She added, “We never talked labels, like lesbian and gay. We just lived our lives, and I hoped it could go on that way forever.” Crawford confirmed that Houston broke off the relationship when she signed her record deal with Arista in 1983. "She said that if people find out about us, they would use this against us, and back in the '80s, that's how it felt.”

Was Whitney Houston bisexual? Was she a teenager exploring a side of her sexuality? We’ll never know. What we know for sure is that any feelings were quickly shut down by societal pressure — and all that marketing. Most importantly, we know that being forced to hide parts of ourselves has a lasting emotional impact. A study conducted by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) found that bisexual people are more likely than heterosexuals to experience major depressive episodes and thoughts of suicide and are two to three times more likely to use illicit drugs. Compared to gay and lesbian respondents, bisexual people are one and half times more likely to report suicidal thoughts and attempts.

Only worsening things for Houston is that, as newly crowned pop royalty, she embodied the pressure that Black people feel to be exceptional in order to be accepted by a dominant white culture. Houston’s crossover appeal made her the first recording artist to earn seven consecutive No. 1 hits (one more than the Beatles) and the first woman to generate four No. 1 singles off one album. Studies also show that when an underrepresented group of people have to consistently “code switch” as a survival mechanism, it can lead to psychological fatigue and burnout.

But Whitney Houston, the brand, represented a lot of things to lots of people.

The good girl. She came from a famous family. Her mother was an acclaimed gospel singer, and Dionne Warwick was her cousin.

The trailblazer. Michael Jackson dismantled the color barrier on MTV for Black men and Houston did the same for Black women. With the success of “How Will I Know,” she became the first Black woman to receive heavy rotation on the channel, paving the way for artists like Janet Jackson and Anita Baker.

The meal ticket. She was sued twice by family members, including her father in 2002 for a payment dispute over the negotiation of her contract renewal with Arista Records. The suit was thrown out two years later. She was sued again by her step-mother in 2008 because Houston was the beneficiary to a life insurance policy after her father died.

Houston was never allowed to be wholly human, always hiding parts of herself to please others, especially the audience in front of her. Acceptance was always conditional.

As Houston’s substance abuse worsened, it became more difficult to code-switch between personas. She became easily agitated in interviews, and her public behavior became more erratic. The impact of having to preserve her image was taking its toll.

Crawford remained Houston’s closest confidante until her friend’s substance abuse and tumultuous marriage to Bobby Brown became too much to bear. Crawford resigned as Houston’s creative director in 2000 and distanced herself from the inner circle.

"No matter what rules we came up with around responsible drug use, she kept breaking them and using whenever she wanted to," Crawford wrote in her memoir.

Houston died of an accidental overdose in 2012.

In 2022, a biopic was released called I Wanna Dance With Somebody. The film fully acknowledges Houston’s queer history with Robyn Crawford. "The thing I loved about her relationship with Robyn is that it's just the deepest connection I think that Whitney experienced," said star Naomi Ackie to Entertainment Weekly. Film director Kasi Lemmons told the Los Angeles Times that there were debates with the Houston estate over how to portray the relationship. Eventually, the estate permitted Lemmons to include their romance in the film.

Despite every slight that forced Houston to keep another piece of herself unexplored, she became an icon for empowerment and strength that persists years later.

Her music was so central to the theme of queer resilience and joy that when producer Ryan Murphy was producing Pose, the FX drama about the early days of queer ballroom culture, he changed the entire script to have the show take place in 1987 instead of 1986 to coincide with the release date of “I Wanna Dance with Somebody.” In the pilot episode, an unhoused teen, recently kicked out of his family home, has aspirations of attending a prestigious dance school. The scholarship deadline has already passed and hopes are dashed until a sympathetic department chair is convinced to give Damon an impromptu audition. With no time to prepare, he’s going to have to wing it. Luckily, the only inspiration Damon needs to give the most triumphant performance of his life is a cassette tape of Whitney Houston singing:

Clock strikes upon the hour

And the sun begins to fade

Still enough time to figure out

How to chase my blues away…

Yeah, I wanna dance with somebody

With somebody who loves me.

Note to free subscribers: Substack has limited tiers for paid subscriptions and does not allow for a “pay what you wish” model. If you’d like to support my work by making a small, one time donation, you can do so here. Any amount is appreciated.

Did you catch last week’s issue?

I don't tell you enough how much I appreciate your work! I learn so much from you, and you add an amazing and fresh perspective to songs I've known and loved for years but clearly never understood on quite the same level as you.

Thank you for the thoughtful write up on Whitney. She is on the list of women featured in my upcoming book “First Ladies of Music.”

I think it’s also significant to point out her religious upbringing. She spoke of God often and presumably had a hard time reconciling her faith with her sexuality-- most certainly contributing to her addictive behavior.

Between the inner turmoil and external pressures, one might say it’s a miracle she lived as long as she did.

From a business perspective, it’s another example of personal branding not lining up with reality or personal values. PR machines gone wild. This almost always leads to devastating outcomes professionally and/or personally. Tiger Woods, Charlie Sheen, Demi Lovato, Marilyn Monroe, and the jury is literally still out on Lizzo. The list goes on.