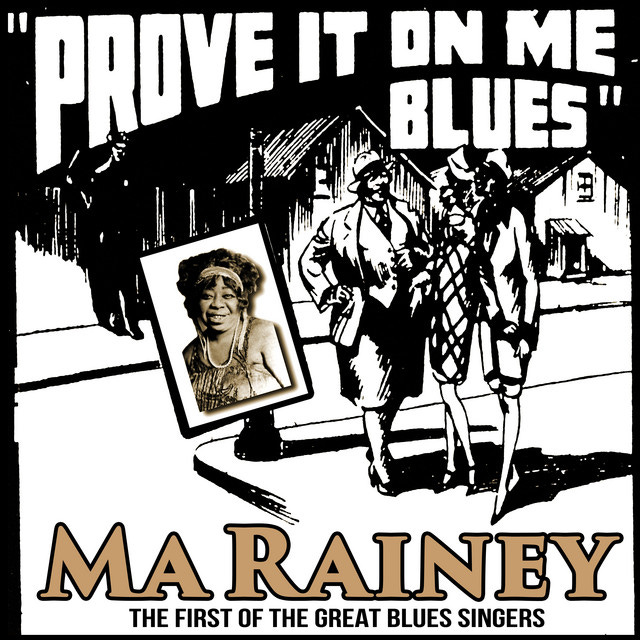

"Prove It On Me Blues" - Ma Rainey

On Origin Stories

Ma Rainey didn’t invent rock n roll, but she was the template.

A liver full of gin, a mansion filled with groupies - throw in a few orgies and a not-insignificant arrest record and you’ve got yourself a rock star. But who invented the rebellious, freewheeling image we associate with so many names? In the ‘60s, the votes might go to Keith Moon, who once drunkenly knocked out his own front teeth, or Jim Morrison, who decades after his death has more than 20 paternity suits pending against him. The late ‘50s gave us the libidinous Jerry Lee Lewis, who was married seven times — once to his 13-year-old cousin— and who once burned his piano to the ground when Chuck Berry got top billing at a show.

To find our true blueprint, we have to go back further — the 1920s. If rock n roll was born from the blues, then the opulence and swagger of the rock star were traits inherited from its parent — or specifically, its “mother.”

Three decades before rock n roll, its ostentatious, orgy-loving persona was invented by a queer, Black woman named Gertrude “Ma” Rainey.

“Have you ever been drunk, slept in all your clothes? And when you wake up, feel like you want a dose?” - “Dead Drunk Blues.”

Nicknamed the “Mother of the Blues,” Ma Rainey was among the earliest blues artists ever recorded and helped create what is now known as “classic blues,” which combines traditional folk blues with elements of vaudeville. Because of her raucous humor, boisterous stage presence, and raw lyrics, Rainey became one of the biggest celebrities of the 1920s. She was also among the first Black artists to play for racially integrated audiences. Author Sandra Lieb of Mother of the Blues: A Study of Ma Rainey observed that “Rainey offered to whites a glimpse into Black culture far less obscured by white expectations, and offered to Blacks a more direct affirmation of their cultural power.”

Everything about Rainey’s persona would become the template for rock n roll and, later, hip-hop. Her deep, gravel-like voice inspired imitators like Louis Armstrong, then Janis Joplin and Bonnie Raitt. Her pioneering fashion choices — which included wearing ostrich feathers, sequined gowns, diamond tiaras, and gold teeth — can be traced throughout rock and hip-hop’s most decadent characters like Elton John, David Bowie and Lil Nas X. She was sporting gold chains long before Lil Wayne invented the term “bling.” Rainey’s songs celebrated the sexuality of Black women and bucked the heteronormative concept of “acceptable” behavior. In her 1999 book Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, Angela Davis wrote that Rainey's songs are about women who "explicitly celebrate their right to conduct themselves as expansively and even as undesirably as men." Characters in Rainey’s music are fearless, promiscuous, and take no shit. Rainey’s own sexual appetite landed her in jail for hosting a “women-only” orgy. She was bailed out by protégé and former lover, Bessie Smith. “Cuz girls is players too,” boasts Coi Leray, a hip-hop artist whose image wouldn’t be possible today without Rainey.

Born Gertrude Pridgett, Rainey began her career at the age of 12 as a performer in minstrel shows. Her career book-ended a seismic event in music history — the development of song recording. Unlike many vaudeville performers, Rainey’s success continued to skyrocket when sound recording on vinyl was invented partly due to the growing demand for songs by Black musicians and the rapid ascent of blues’ popularity. Rainey was signed to Paramount in 1923 and made more than 100 recordings in five years. Her celebrity status elevated blues as a national genre beyond the boundaries of the South.

The notion that a Black woman could be responsible for spearheading a genre of music that would give rise to American jazz — and, ultimately, rock n roll — is incredible. But what’s truly amazing is that the blues’ highest-paid star also sang unapologetically about queer life in the 1920s.

“Bo-Weevil Blues” (1923)

I don’t want no man to put no sugar in my tea

I don’t want no man to put no sugar in my tea

Some of them are so evil, I’m ‘fraid they might poison me.

Rainey’s reference here isn’t explicitly queer, but it seems to imply that if she doesn’t want a man to “put sugar in her tea,” perhaps she’d rather a woman did it instead.

“Shave ‘Em Dry Blues” (1924)

The title, “Shave ‘Em Dry,” is a reference to foreplay-less, aggressive sex.

Here’s one thing I don’t understand,

Why a good-looking woman likes a workin’ man,

Hey, hey, hey, daddy, let me shave ’em dry.

Rainey is suggesting that men aren’t as good at sex as she is and later references her more “butch” side by talking about peers dressed in men’s “brogan shoes,” footwear that wouldn’t be worn by any woman unless she was cross-dressing or gay in the 1920s.

Goin’ downtown to spread the news,

State Street women wearin’ brogan shoes

Sissy Blues (1926)

In “Sissy Blues,” Rainey tells a story of her boyfriend cheating on her with another man.

I dreamed last night I was far from harm

Woke up and found my man in a sissy's arms

My man's got a sissy, his name is Miss Kate

He shook that thing like jelly on a plate

“Prove It on Me Blues” (1928)

As opposed to her other nods to homosexuality, which were sprinkled sparingly, “Prove It on Me Blues” is a direct reference to her queerness.

Where she went, I don’t know

I mean to follow everywhere she goes;

Folks say I’m crooked. I didn’t know where she took it

I want the whole world to know.I went out last night with a crowd of my friends,

It must’ve been women, ’cause I don’t like no men.

According to the website queerculturalcenter.org, the lyrics refer to an incident in 1925 when Rainey was "arrested for taking part in an orgy at [her] home involving women in her chorus." At the time, an ad for the song embraced the genderbending outlined in the lyrics and featured Rainey in a three-piece suit, mingling with women while a police officer lurks nearby.

They said I do it, ain't nobody caught me

Sure got to prove it on me.

It’s true I wear a collar and tie.

Makes the wind blow all the while

“Prove It on Me Blues” is considered one of the earliest gay anthems in history and is remarkable not only for its sexual honesty but also for the blatant nose-thumbing at law enforcement. Queer sexuality was heavily policed in the 1920s — even more so for Black and Brown people — and violence from law enforcement was a constant threat.

Actress Viola Davis, who portrayed Rainey in the 2020 film adaptation of the 1982 play, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, spoke to The Advocate about Rainey’s legacy. "She was unapologetic about her sexuality. This is a woman who went to orgies. I felt like Ma always had a woman with her. That was her world. I didn't want to sweep it under the rug."

Although Davis’ performance earned her a Best Actress nomination, the script's adaption from the play by acclaimed playwright August Wilson perpetuates a harmful depiction of queer relationships, one that suggests women used Rainey solely because of her celebrity status. The film’s queer romance paints her love interest, Dussie Mae, as a gold digger who’d rather sleep with Rainey’s trumpet player, Levee, portrayed by Chadwick Boseman in his final performance. According to The New York Times, “Wilson’s plays are often ruled by men, and Ma is not just a Black woman at the center of her story, but a queer one, an identity otherwise absent in Wilson’s oeuvre. Rarely do gay Black women receive the spotlight, and certainly not in the mid-1980s, when the play arrived in New York. In the theatrical version, Ma has one woman in her entourage with whom she flirts, though she never speaks of sexuality aloud: a notable omission for a character rooted in the Black community, where queerness has historically been, and is often still, marginalized and stigmatized.”

Another biopic co-written and directed by Black lesbian filmmaker Dee Rees offers a more realistic depiction in Bessie, the 2015 biopic about Rainey’s blues protege Bessie Smith. Both Rainey and Smith are played by two queer actresses - Mo’Nique and Queen Latifah. The film depicts both women as charismatic, sexual, and assured of their queerness.

Rainey’s style of classic blues began to wane in popularity with the rise of jazz, and she was fired by Paramount Records in 1928. It’s unclear if she was paid the royalties from her recordings. In 1935, she pivoted to another kind of entrepreneurship when she bought two movie theaters in Georgia. She managed them until her death four years later.

Ma Rainey represented several firsts in rock n roll history. Her boisterous stage presence, decadent fashion, and lewd lyrics created an early blueprint for freewheeling American rock stars, something that was finally acknowledged when she was posthumously inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990. She was one of the first Black artists to sign with a white-owned record label. While other blues singers of the day, like Bessie Smith and Mamie Smith, largely sang songs written by others, Rainey penned at least one-third of the songs she recorded. And she was a queer pioneer, openly dating women and cross-dressing in her performances in early-1900s America. Ma Rainey wasn’t just ahead of her time. She was the template. The personification of a “rock star” is more than just flash, brash, and orgies - it’s about total freedom. And Ma Rainey was free at a time when the privilege of freedom was harder to come by.

Did you catch last week’s issue?

Ma was a class act. You sure got to prove it on me that she's not legendary.

Beautiful. What a legend! I know what I'm listening to today...