The Queer Roots of Punk Rock

On Rebellion

Before It Was Punk, It Was Queer: The Gay Roots of Rock’s Loudest Rebellion.

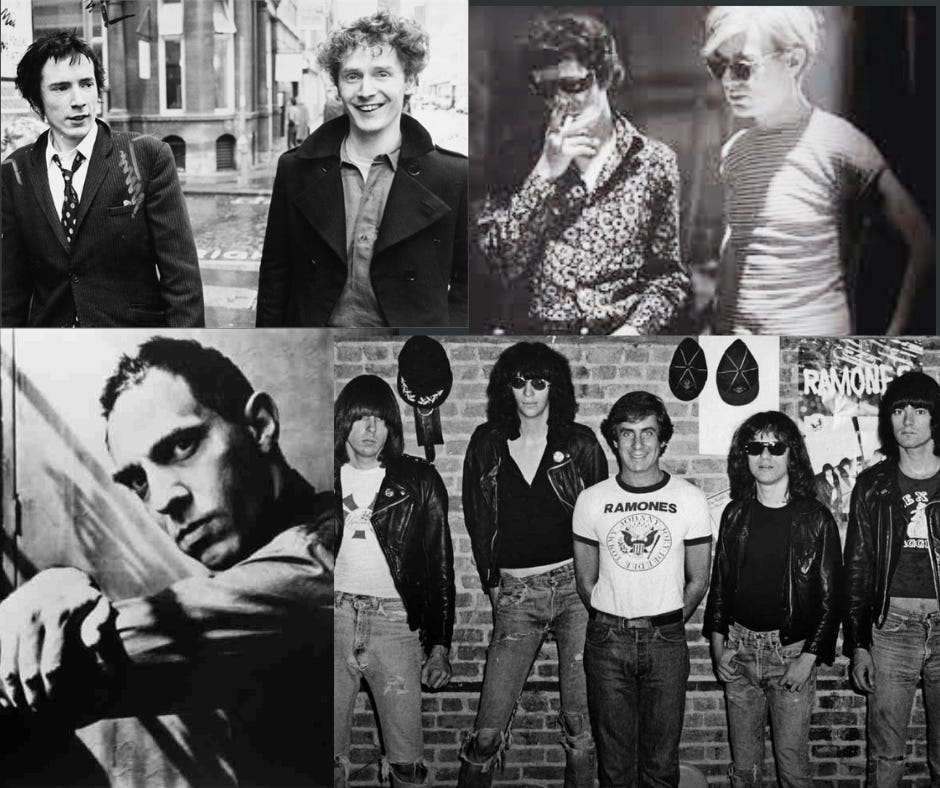

In the mainstream version of punk history, the story often begins in 1976 when the Ramones released their debut album in New York and the Sex Pistols snarled their way across London. But that telling flattens the radical, messy, queer undercurrents that were already shaping the scene long before it had a name.

Punk didn't emerge out of nowhere. It grew sideways out of gay bars, gender-bending drag performance, Warhol’s Factory, and the glammed and glittery performers who saw rebellion as something you wear, scream, and live. Punk inherited its attitude and much of its visual aesthetic from queerness. The lineage from proto-punk bands like the Velvet Underground, the Stooges, MC5, the New York Dolls, and Patti Smith to punk bands like the Ramones and the Sex Pistols can all be traced back to three queer men: Andy Warhol, Danny Fields, and Derek Jarman.

Andy Warhol’s Queer Factory

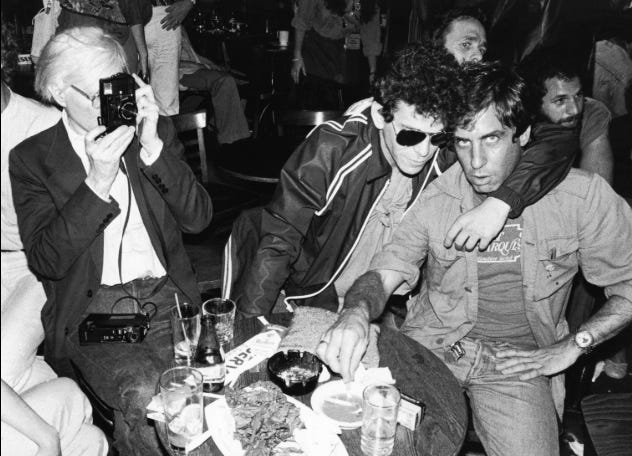

Before punk had a sound, it had an aesthetic, and much of it came from Andy Warhol’s famed art studio simply called Factory, a metallic queer utopia where gender norms and artistic boundaries were irrelevant. In addition to his pop art revolution, Warhol managed the Velvet Underground, who are often considered the earliest prototype for punk. Queer lead singer Lou Reed’s associations with Warhol and trans and genderfluid icons like Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis, and Holly Woodlawn created an early fusion of experimental rock and gender nonconformity.

At the beginning of 1968, Warhol relocated his Factory from 47th Street in Manhattan to Union Square. The move meant that he and his queer troop of Superstars found a new social haunt right across the square, at Max’s Kansas City. Owner Mickey Ruskin had a soft spot for artists and traded free bar and food tabs in exchange for art. It became a popular watering hole for luminaries like Rauschenberg, de Kooning, and many others. Warhol and his entourage took up residence in Max’s back room, and it became New York’s cultural epicenter where the beginnings of punk music gestated. In the book High on Rebellion, Iggy Pop explains the importance of Max’s Kansas City as a cultural phenomenon. “For me, there were two Max’s. The first Max’s was the back room, behavioral New York, gay intellectual performance art. And then there was the other Max’s which became the rock & roll venue. The old Max’s was for me.”

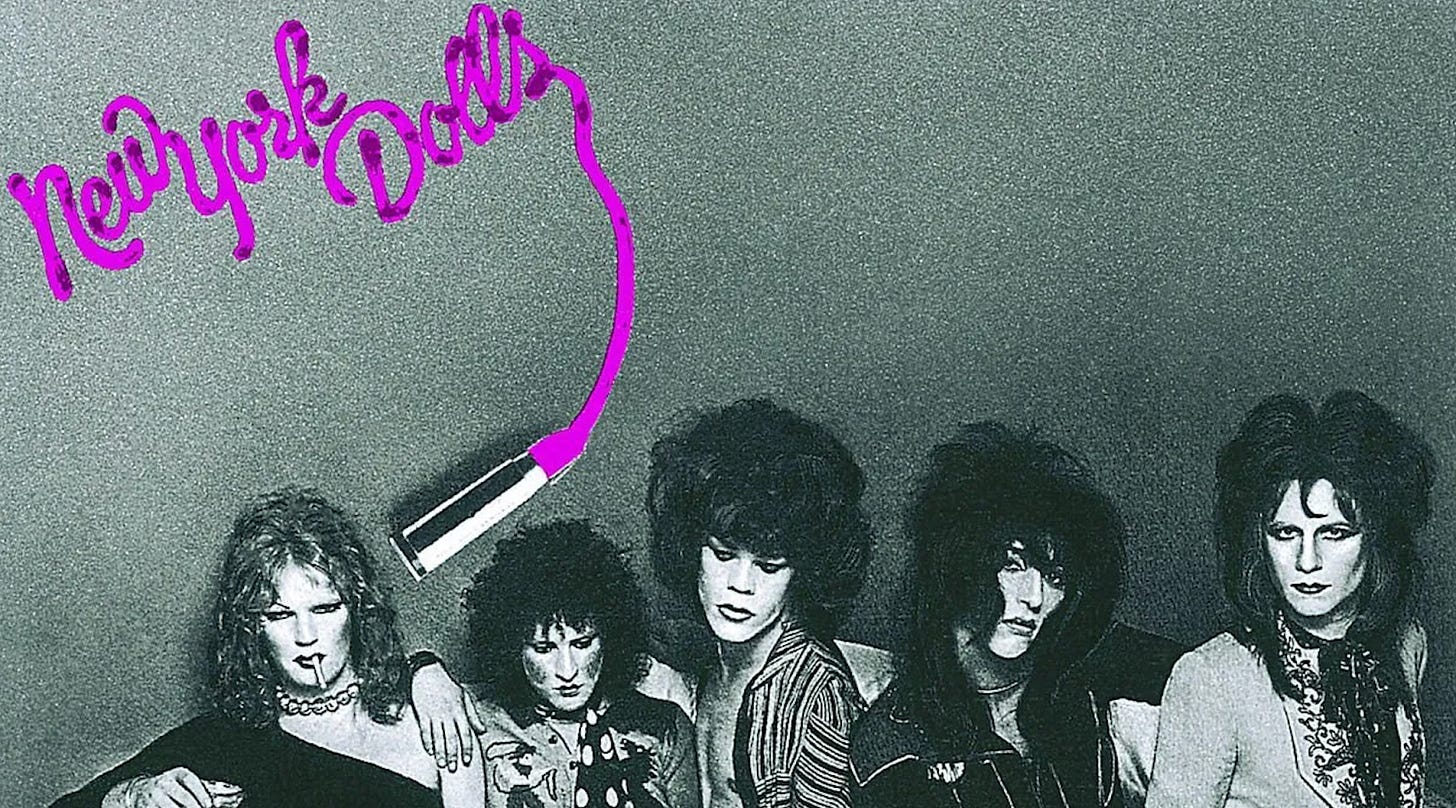

If punk’s grandparents on its father’s side were the Velvet Underground, then on the mother’s side were another band, the New York Dolls. They emerged in 1972 from the apex of connections in Warhol’s world: Max’s Kansas City and the Theatre of the Ridiculous, which brought elements of queer performance to experimental theater. The theatre was famous for casting drag queens and trans actors. “I used to work for this guy in St. Mark’s, Wart Wilson, who had a store in St Marks Place,” said future New York Dolls lead singer David Johansen in the book Secret Public. “He had a basement where he had a workshop and I noticed these racks of costumes. They were for The Theatre of the Ridiculous.” Johansen immediately got a job as a production assistant. “They definitely influenced me. I got a lot from them and Little Richard.” Johansen also had a job as a busboy at Max’s, and it’s out of the combination of these experiences that he molded the gender-bending, cross-dressing, outrageous band that became the New York Dolls.

Leee Black Childers photographed the New York Dolls for Melody Maker, commenting, “They had taken the whole out of the trash look of Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn and somehow made it cute.”

Queer and trans performers weren’t just muses, they were icons of rebellion. They were living embodiments of the “gender as performance” ethos that punk would later weaponize. The Velvet Underground and the New York Dolls didn’t just borrow the look, they carried forward the sexual ambiguity, theatricality, and outsider energy that made early glam rock such fertile queer ground. It’s no accident that when future Sex Pistols manager Malcolm McLaren came to New York in the early ’70s, he tried to manage the Dolls. He later folded their aesthetic into the DNA of the Sex Pistols. More on that in a minute.

Danny Fields: The Queer Connector Behind the Chaos

If punk rock has a godfather, it might just be Danny Fields. He signed or managed some of the most formidable names in punk’s history—the Stooges, MC5, and the Ramones.

Beginning his career as a journalist at the teen fan magazine Datebook, Fields first gained notoriety as the person responsible for spotlighting John Lennon’s infamous “we’re more popular than Jesus” quote in 1966, prompting southern Christians in the U.S. to burn their Beatles records. Around the same time, Fields began frequenting Max’s Kansas City. It was there that he developed connections to Warhol’s social circle. Max’s didn’t have live music until 1969. And it was Fields who brought in the first bands. By then, he was a publicist at Elektra Records. He brought in Alice Cooper, the Stooges, and the Velvet Underground. “He seemed to be at the pulse of the underground,” remarked Alice Cooper in the documentary Danny Says, which chronicles Fields' career. “Lou Reed, Iggy, the whole Warhol gang. He was sort of the mayor of New York City.”

In 1975, Fields discovered the Ramones at CBGB and helped get them signed to Sire Records. It was Fields' own mother who paid for the Ramones' first proper drum kit. As the band's co-manager, with Linda Stein, Fields brought the Ramones to London in 1976, which inspired the fledgling punk movement and bands like the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the Damned.

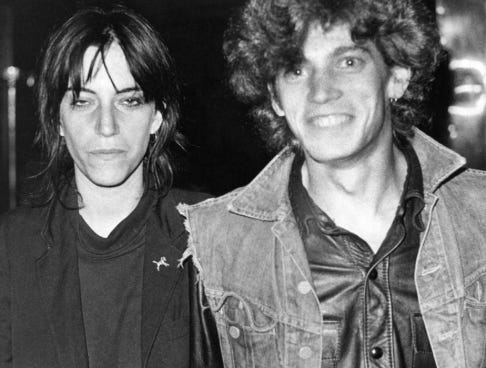

According to Danny Says, Fields claims to have also connected Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe to the music scene via the back room of Max’s Kansas City. “Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe knew about Max’s but they were terrified. It seemed so impenetrable, especially the back room. Everyone was so cool. We’d say ‘there are those cute people again. Which is a boy and which is a girl? They’re just standing there. They look like they want to meet us. At one point, I just went over to them and said ‘sit down! You’re here all the time. Why don’t you sit down and have a cup of coffee. It’s free.’ That was their kick off.” Fields also introduced Smith to Richard Sohl, who would eventually join her band.

Fields isn’t talked about enough, mostly because he was behind the grand curtain of some of rock & roll’s most important bands. But it was Fields who connected the dots between queer performance art, glam, and proto-punk rawness. As The New York Times once wrote, “You could make a convincing case that without Danny Fields, punk rock would not have happened.”

Derek Jarman’s Punk Dystopia on Film

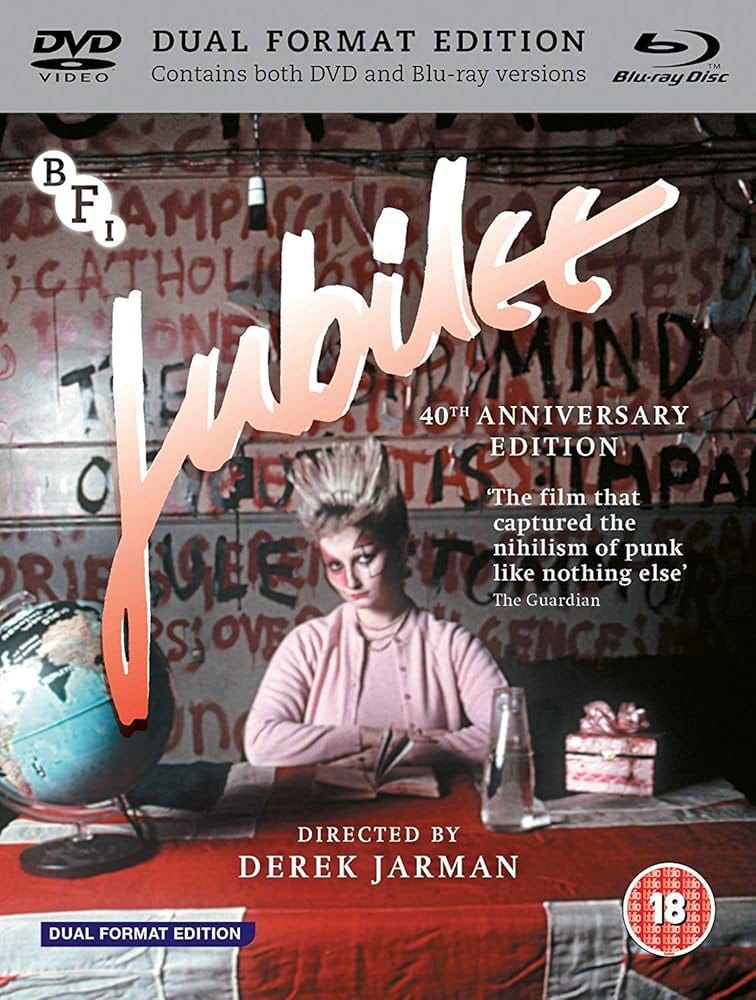

Few captured punk’s queer potential as unapologetically as filmmaker Derek Jarman. His 1978 film Jubilee was described by the Bright Lights Film Journal as “Britain’s only decent punk film,” but it’s more than that. In Jubilee, Queen Elizabeth I travels forward in time to witness the bleak, crumbling state of 1970s Britain, ruled by her namesake descendant and overrun by punks, misfits, and queers. The film features cameos from trans punk icon and former Max’s Kansas City house DJ Jayne County, as well as Adam Ant, Siouxsie Sioux, and The Slits, and it includes performances that blur the line between stage and riot. Jarman, who had already directed 1976’s Sebastiane, one of the first British films to center gay sexuality and religion, was less interested in punk as a genre and more so as a political statement. To him, punk was a queer rejection of empire, patriarchy, and conformity.

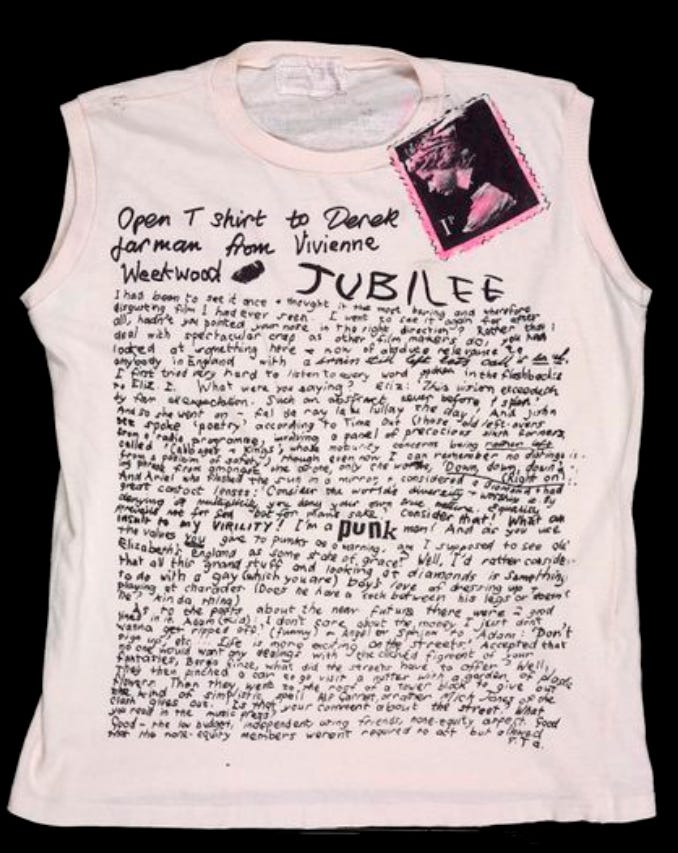

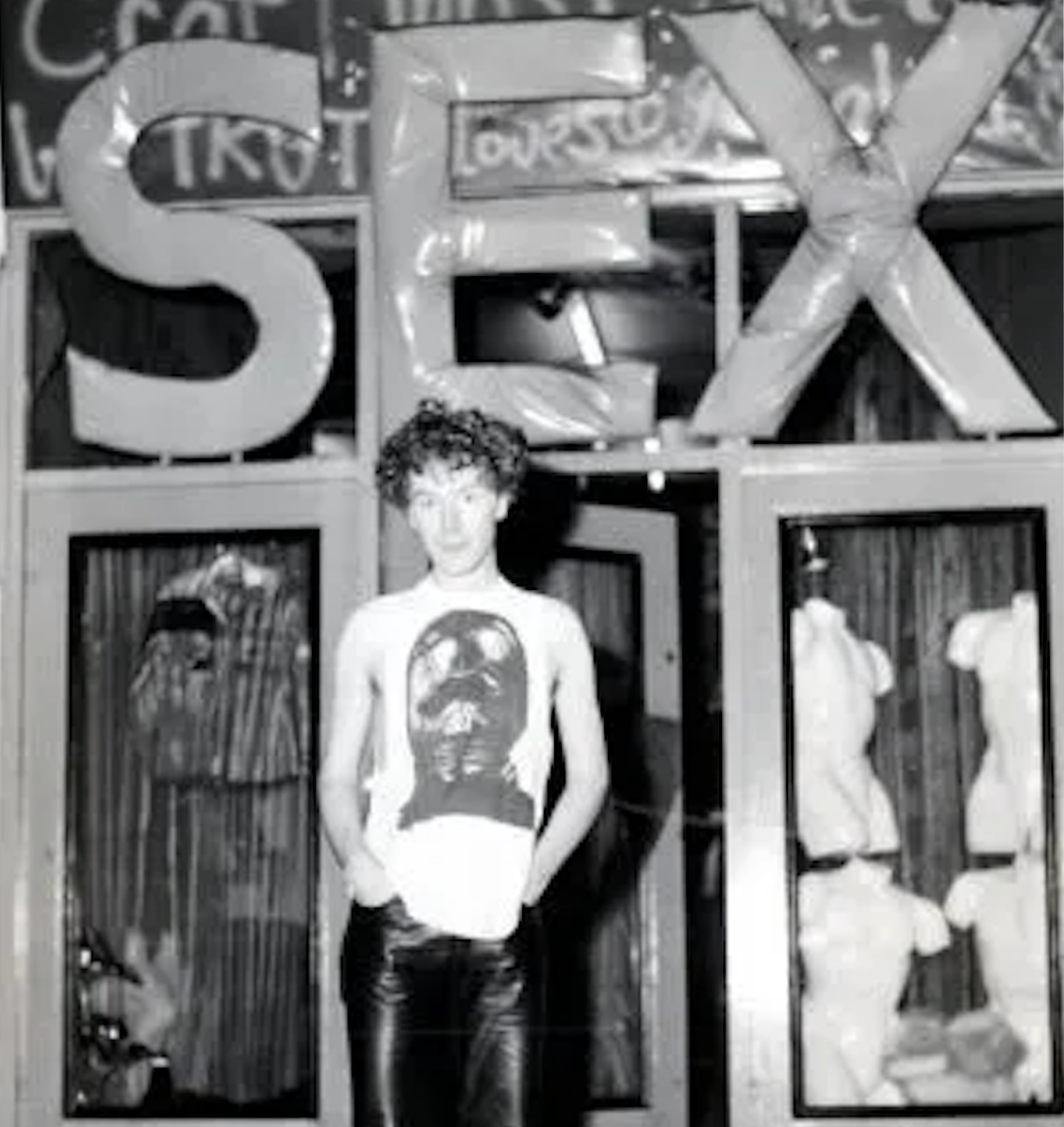

The film elicited a very punk rock response from fashion designer Vivienne Westwood, who along with partner Malcolm McLaren, were at the center of punk’s infancy. Westwood and McLaren owned SEX, the London boutique that would become the standard aesthetic for England’s punk scene. On a white cotton sleeveless shirt, now housed in the V&A Collection in London, Westwood scrawled out paragraphs of vitriol toward Jarman and his criticism of punk’s apocalyptic future.

“I am punk man! And as you use the valves you give to punks as a warning, am I supposed to see old Elizabeth’s england as some state of grace? Well, I’d rather consider that all this grand stuff and looking at diamonds is something to do with a gay (which you are) boy’s love of dressing up & playing at charades. (Does he have a cock between his legs or doesn’t he? Kinda thing)”

That Jubilee sparked a public feud between Westwood and Jarman is less surprising with some context. Not only did Jubilee actor Jordan, in the role of the brazen punk protagonist Amyl Nitrate, work for Westwood at the time (Jarman met Jordan behind the counter of SEX), but historian Jim Ellis also suggests that Amyl Nitrate was Jarman’s unflattering depiction of Westwood.

Jarman would go on to direct several music videos for bands like the Sex Pistols, the Smiths, Pet Shop Boys, and Patti Smith.

Malcolm McLaren and the Appropriation of Queer Style

Many people credit the couple Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood and their boutique store SEX as the catalyst that launched punk in England. But most of McLaren’s ideas were taken from what he observed in New York. According to the documentary Nightclubbing, McLaren started the Sex Pistols after trying unsuccessfully to manage the New York Dolls. He personally checked into rehab Dolls’ guitarist Johnny Thunders, drummer Jerry Nolan and bassist Arthur Kane so he could organize a tour for them throughout the U.S. The point for McLaren was to advertise the fashions sold at SEX. Tampa was the tour’s first stop. Except the problem was Thunders and Nolan wanted to score heroin and found that somehow difficult in Florida, so they left to return to New York. With a management gig that failed before it began, McLaren went back to London with some valuable lessons. After a failed attempt to turn the New York Dolls into a walking billboard for his fetish-fashion boutique SEX, McLaren had a new plan. He fused the Dolls’ campy nihilism with the Ramones’ three-chord minimalism and the flamboyant provocations of gay liberation movements. The result? The Sex Pistols.

The Pistols were a marketing experiment—but one grounded in the rebellion of queer aesthetic. The band’s earliest fans, nicknamed the Bromley Contingent, were a group of queer kids (including Siouxsie Sioux and Billy Idol’s entourage) who frequented queer bars like Louise’s, a lesbian club that welcomed London’s first wave of punks. McLaren’s store sold shirts emblazoned with gay pornographic imagery and slogans pulled directly from gay liberation literature, like “Out of the bedroom and into the streets.”

When Pistols guitarist Steve Jones wore one of these shirts in public, he was arrested under an 1824 vagrancy law. “They got me purely on the gay imagery, thinking I was a rent boy. They have no conception of fashion,” Jones says in the book Secret Public.

In a 2002 interview, McLaren admitted that his best ideas were borrowed from the queer scene in New York. “I was very happy to bring a piece of New York back. I didn't see the Sex Pistols as anything more than a vehicle, at that time, to basically push the boat out from the shop, it was just a wonderful little idea that I cared about because I thought, wow, to try and make an anti-music statement. What I'd seen, what I'd been swept off my own feet from, with the New York Dolls, what I'd discovered in the whole S&M scene, this idea that, yeah, you could get kids to really experiment with their sexuality, the look of all that, the black leather, the studs, the tit-clamps, the dog-collars, the whole S&M process and style that was harbouring around Christopher Street at the time, the New York Dolls were coupling up with pearl necklaces and little girls' sweaters... I kind of liked all the trashiness of that and I was very taken with it.”

The early punk scenes in both New York and the UK were deeply rooted in queer spaces. Before the genre hardened into something marketable, punk bands played in gay clubs like Mother’s near the Chelsea Hotel in Manhattan where the Ramones, Blondie, and Suicide performed. In London, it was Louise’s and in the North it was The Ranch, a tiny Manchester gay bar that gave a home to the Buzzcocks and others. As Pete Shelley of the Buzzcocks remembered in the book Secret Public, “Gay bars were the places you could go and be outlandish with your dress and not get beaten up.” Siouxsie Sioux called early punk a “club for misfits - anyone who didn’t conform to any mass Mecca… male gays, female gays, bisexuals, nonsexuals, everything. No one was criticized for their sexual preferences.”

And yet, by 1977, the music industry tried to shove punk into a more heteronormative frame. Gay people were pushed toward disco; rock was rebranded as straight. Punk's queerness, its origin point, was brushed aside for marketability. The new punk attitude oscillated between outright hostility and the denial of its gay beginnings.

The early years of punk were not just accidentally queer. They were built by queer people—artists, managers, designers, filmmakers, and fans who turned marginalization into fuel. It’s time to remember that before punk was loud, it was queer.

If you’ve learned something from this publication, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. And stay tuned for Jami’s radio episode on this same topic (but including all of the amazing music!) which will be available on Thursday. Thanks for reading and supporting my work.

If you want to dive deeper into some of the source material I used when researching this article, check out the books Secret Public and High on Rebellion and the documentaries Danny Says and Nightclubbing.

Right on, as usual. I got the first Dolls album the week it came out. Hugely important.

Excellent write-up as always, Jami. I’m sure some readers will be surprised by this one. It’s yet another reminder of just how deeply the LGBTQ scene in New York shaped the course of music history.